POST

INTENSIVE LANDSCAPES

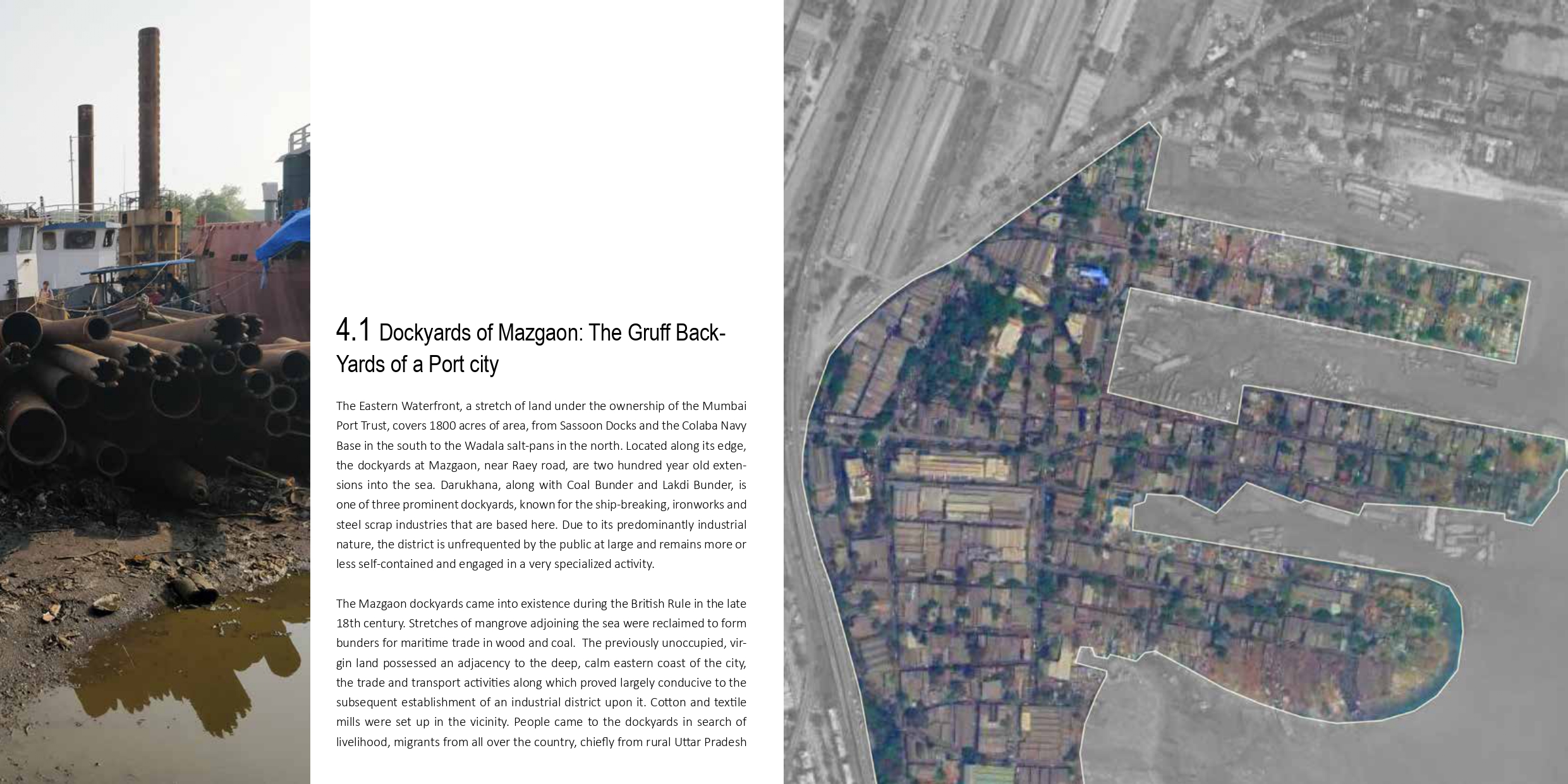

Landscapes produced as a result of intensive human activity such as mining-quarrying sites, salt pan lands, garbage dump yards, industrial wasteland, lands arising from intensive agriculture are generally seen through the lens of chemical degradation and environmental pollution. Here, the research, assigns the term 'post-intensive landscape’ to describe these landscapes that have moved past the stage of intensive human activity and we try to set-up criteria to identify the same. By doing this we aim to examine the factors that lead to the creation of such landscapes and the larger processes they symbolize post their creation. By acknowledging such lands and the circumstances of their production, we seek to investigate the challenges of our current understanding of what inhabitations of these landscapes mean.

References

Di Palma, Vittoria. 2016. “In the mood for landscape.” In Thinking the Contemporary Landscape, edited by Christophe Girot and Dora Imhof, 14–32. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Sassen, Saskia. 2016. “Land as infrastructure for living.” In Thinking the Contemporary Landscape, edited by Christophe Girot and Dora Imhof, 33–41. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Bhatia, Neeraj and Casper, Mary. 2013. The Petropolis of Tomorrow. New York: ACTAR and Rice School of Architecture.

Allen, Smout. 2016. “Augmented Landscapes.” In Pamphlet Architecture 28, edited by Scott Tennent, 5–21. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Corner, James. “Recovering landscape as a critical cultural practice.” In The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner 1990-2010, edited by James Corner andAlison Bick Hirsch, 111–29. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Kirkwood, Niall. 2001. Manufactured Sites: Rethinking the Post-Industrial Landscape. xxxxx: Taylor and Francis.

Hollander,Justin; Kirkwood, Niall and Gold, Julia. 2010. Principles of Brownfield Regeneration: Cleanup, Design and Reuse of Derelict Lands. Washington: Island Press

Engler, Mira. 2004. Designing America's Waste Landscapes. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press

Lin, Dejun, Steven. 2015. Drosscape resilience : from coal mine waste dump to performative ground. Pokfulam, Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong

Di Palma, Vittoria. 2014. Wasteland, A history. xxxxx: Yale University Press

Storm, Anna. 2014. Post Industrial LandscapeScars. New York: Palgrave Macmillian

Tang,Dorothy & Watkins, Andrew. 2011 “Ecologies of Gold,” Places Journal, Accessed 04 Oct 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/110224

David T. Hanson. 2011, “Colstrip, Montana,” Places Journal, Accessed 04 Oct 2021. <https://placesjournal.org/article/colstrip-montana/>

Karen Lutsky and Sean Burkholder. 2017, “Curious Methods,” Places Journal, Accessed 04 Oct 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/170523

Mark Feldman, 2012. “Visualizing the Ends of Oil,” Places Journal, Accessed 04 Oct 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/120426

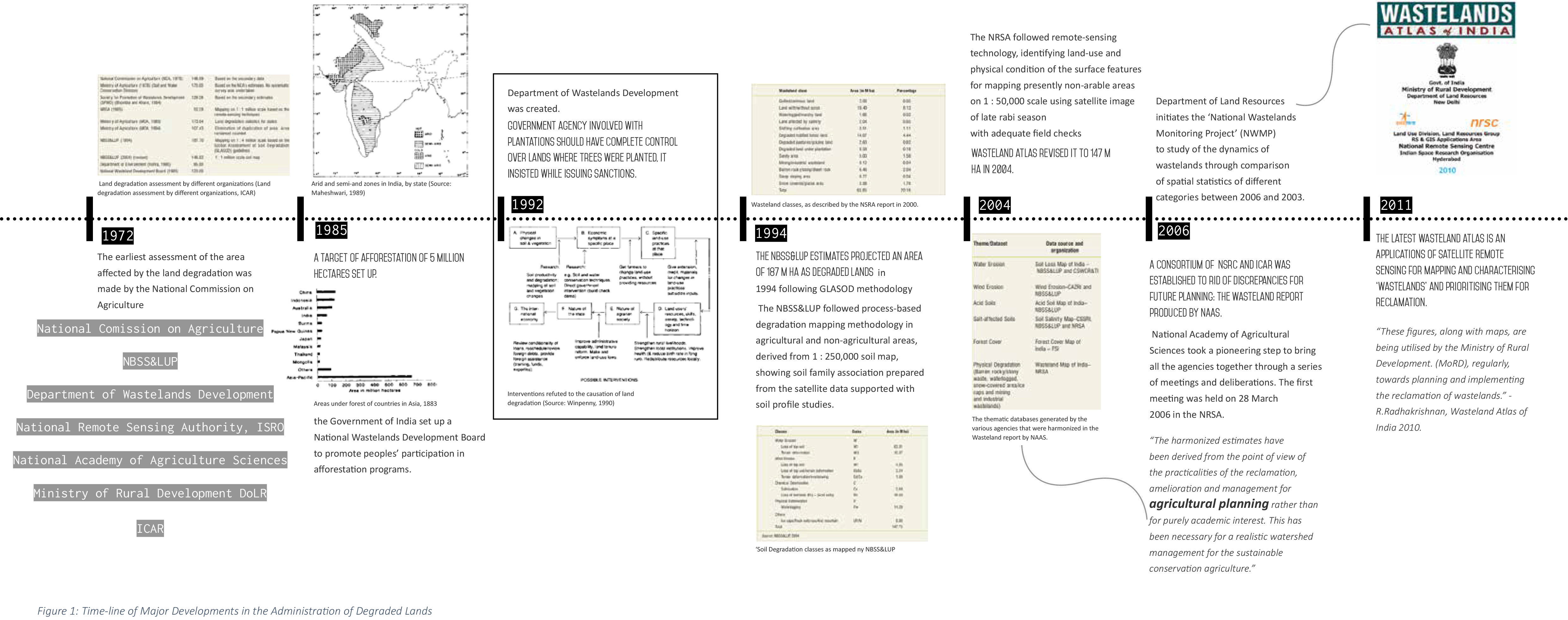

Timeline of Major Developments in the Administration of Degraded Lands

METHODOLOGY

Land, and the development of it, is not a product of objective history. The research aims to identify landscapes that have undergone intense human activity and are altered and degraded due to extensive human use, through supposition, personal accounts, historical data, and popular media to create a unbiased, interpretable account or ‘story’ of the land. The research does not stick to a language of policy making and planning in a historical and visual narrative, treating landscapes as metaphors, allowing accounts to be more descriptive, and avoiding allegiance with existing factions within the environmental narrative. The format of the ‘story’ is provocative rather than instructive and mobilises fiction and magical realism, and the research intends to raise questions when it comes to understanding new ecologies as systems that refute existing notions, especially in relation to their futures under a bio social framework of looking at such landscapes. From a glossary of wastelands identified in the country, cases that represent various kinds of post-intensive landscapes are shortlisted and studied in detail. They would form the case studies through which the questions regarding the environment and the idea of inhabiting ‘new natures’ is addressed, expressed as ‘Stories of the land’ and ‘Stories of the Futures Present’. These would map/comment upon how do popular narratives resource exhaustion or resource threat manifest in the spatial habitation of land, and spatial change over time, which in itself is a result of culture and also creates new culture and relationships. The methodology used to study these places is mostly ethnographic interviews, survey of secondary sources and observation, drawing out of stories in various forms.

A. Lands degraded from resource extraction: A resource-rich region left completely or partially barren post the depletion of the resource.

1. Mining Sites

2. Quarries

3. Sites subject to Over-grazing

4. Deforested sites

B. Contaminated Landscapes: Lands that are polluted, rendered unproductive or unsuitable for inhabitation due to physical or chemical contamination.

1. Industrial Sites

2. Lands polluted due to agriculture

3. Dumping grounds

4. Land-fills

C. Altered Landscapes: Lands that are permanently altered in physiology or geomorphology due to human action, resulting in the creation of an entirely new ecosystem in the region.

1. Flood affected lands due to construction of dams

2. Reclaimed lands

POST INTENSIVE LANDSCAPES 2017-2018

In an age that demands an ever-increasing supply of resources for consumption by a growing population, the present environmental narrative, echoes a persistent global lamentation relating to impending resource exhaustion. Land, both as holder of valuable resources and a resource in itself, is often a subject to such alteration after intensive, prolonged, human use. Such lands, will eventually get utilized to the point of exhaustion and lose productivity, leading to their subsequent abandonment. These altered, distinct lands possess a wilderness that is manufactured as a by-product of intensive activity. As the original stakeholders involved in this process of use and disuse find greener pastures, these landscapes lie as marginal ecologies, awaiting an anxious future.

Since it becomes difficult to determine how to deal with these lands in terms of what they should become, their present state poses serious architectural and environmental questions to planning and development authorities, and to society at large, especially if land itself is a scarce resource in a particular region. Once the resource is exhausted, what does one make of ‘land’? Has land come to be seen as ‘commoditized’- merely a means towards an end, only a resource when it is untouched?

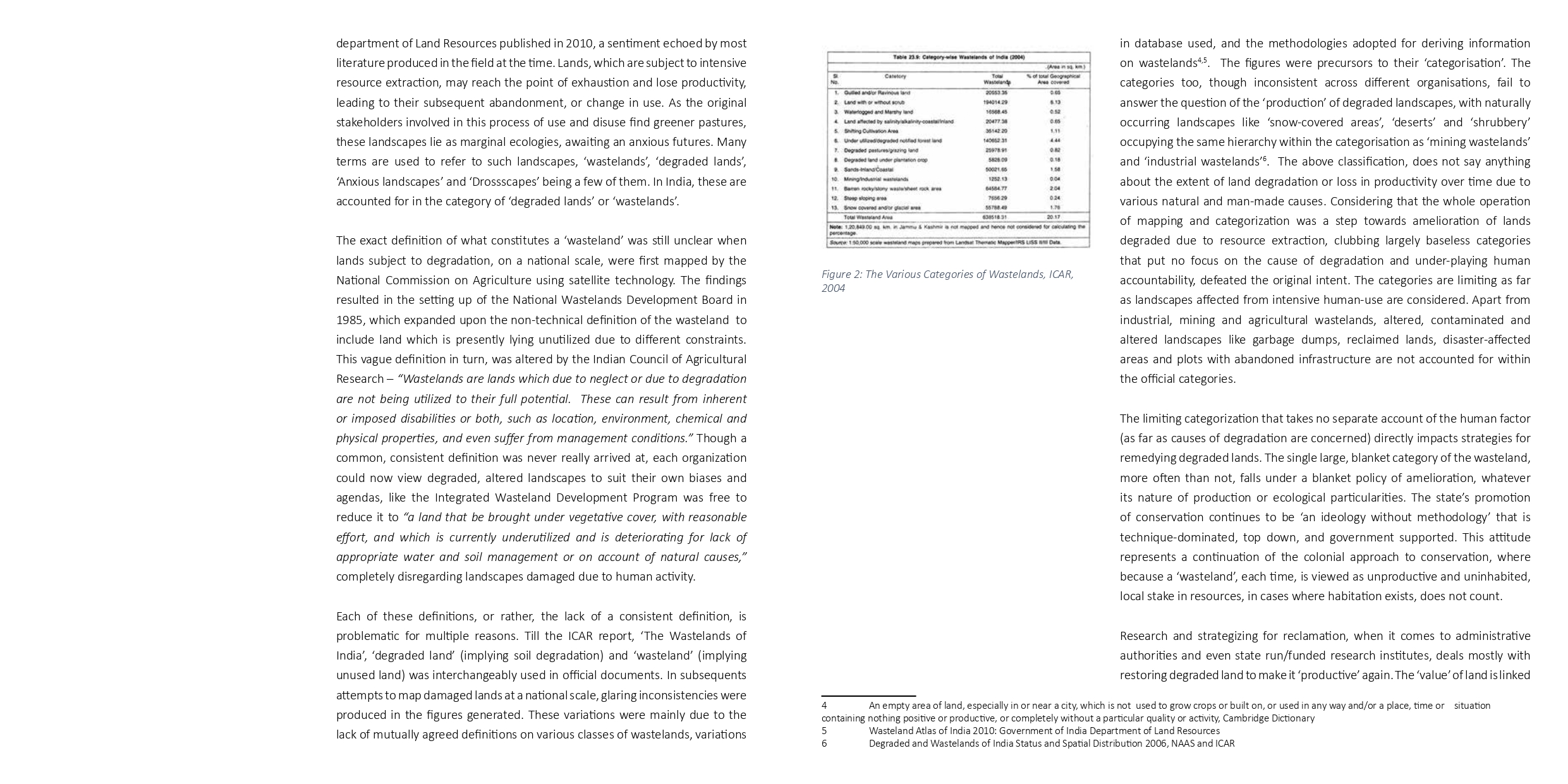

In India, presently, all lands that are unproductive, irrespective of how they came to exist, are put into a single category of ‘Wasteland’, the definition of which is limited.

In India, presently, all lands that are unproductive, irrespective of how they came to exist, are put into a single category of ‘Wasteland’, the definition of which is limited.

This generalized description eliminates human accountability, and provides no distinct method to deal with these landscapes resulting from intensive human use. ‘Treatment’ and ‘restoration’ of degraded lands is a concept that has largely deals with restoring agricultural productivity, and does not account for the spatial and socio-cultural alteration, especially in degraded landscapes in urban areas. If one hasn’t already abandoned the notion that landscape should somehow be beautiful too and imposing, one will surely have difficulties getting something out of such ravaged landscapes. The research aims to examine the new spatial types and uses that arise in relation to these lands, and the architectural questions these pose.

Futures Present:

New natures of Sonshi’s (post) extractive landscapes 2018- 2020

Kavlo has toiled to revive his paddy farms and is worried about the future of his hamlet which is nestled amidst the water-filled, martian craters and blue tarpaulin mountains covering iron ore rejects. Most villagers here have lost their income because of the mining ban. He lives in the madhlya wado and represents the oldest inhabitants of the Adivasi Gawda community, known for their prowess in cultivating khazan fields and practicing shared land rights over village land. Trucker another resident, lives in the Khalchya wado and represents migrants who, after the 1940s, settled in Sonshi from states across India and work tenuously as truck drivers or manual labourers.

Bhatcar another actor forbids Kavlo to enter and cultivate his paddy farms and orchards. Bhatcar lives in the varchya wado and represents Goa’s Desai community of Konkani Maratha moneylenders who were introduced by the Portuguese rule as land administrators and tax collectors under the communidade law. This relegated the Gawdas’ as tenants who tilled land. Company- one of the cats, wants to continue mining and sell the soil beneath these blue mountains. While the newly planted nilgiri reminds him Sarkar who hopes to use afforestation to turn the hilly mining landscape to its pristine condition.

To this, he wonders, ‘What does the future hold for us?’

On his stroll to calm his anxiety he passes the village commons and abandoned mines. Here his senses open to unusual sights of the supposedly disappeared long tailed devil langur. Towards the mining pit he hears a thunderous splash of the sharp toothed magar probably feasting on rohu and katla. He wonders, “When did this change take place?” He realises that several non-human species - the small fish - quietly took over the woods while big cats squabble to reshape the hilly, mining territory.