Architectures of

(ex) foliation

Architectures of (ex)foliation is a heuristic device to inquire into the myriad ways in which monsoonal wetness weaves in urban life and engage with democratizing climate action in coastal cities, especially in the Global South. In a meantime of climate action plans and infrastructures being put into place in coastal cities such as Mumbai, stories of the ‘ordinary’ visions and ‘everyday’ practices of a majority of people are often drowned out by the announcement of ecological emergencies and visions of expert planning. We thus ask: How can stories from Mumbai’s differently situated climate experiences, practices and knowledges be drawn into a creative conversation towards democratizing climate action dialogue? In this project, we seek to democratize climate action by exploring intersections of the social life of urban infrastructures and infrastructural visions, wet ontologies of habitation, and the avenues of urban participation through which infrastructures, builtform and futures get (re)made.

Foreward

In the backdrop of a gathering storm of changing weather and rising seas, the current conversation on Mumbai’s future sketches extreme ends of a teleological future. The protagonists of this conversation have delved on four kinds of actions in response to sea-level rise projections for 2050: first, infrastructures in the form of widening water courses and constructing tall, concrete retaining walls along their edges to drain monsoonal waters away from land; second, “slum” demolitions along water courses to increase capacities for draining monsoonal waters; third, enmasse city relocation and resettlement on a higher ground; and fourth, post-apocalypse scenarios of a submerged city for leisure activities. Such a conversation attempts to futureproof the city for a post-weather tipping point but, in the process, weakens and even dislocates the claims of majority households in the present. Moreover, the imaginations of infrastructures in these conversations, largely predicated on containing water and making the city dry, actually end up making the city either more vulnerable to “natural” disasters or shift the existing problems elsewhere.

It thus comes as no surprise that some scholars have begun to call upon Mumbai’s residents and leaders alike to demand for a climate action plan that is not only ambitious and imaginative but also just. But, in the meantime, how do majority households experience, respond to and innovate in the process of inhabiting monsoon’s everyday wetness and its extreme events in Mumbai?

Despite environmental improvement efforts that have often harmed them, a majority of households are engaged in a series of practices and measures to live with wetness, and adapt to climate and ecological uncertainty in Mumbai. Spatial thinking has remained severely limited in understanding and engaging these ‘ordinary’ visions and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation that are likely to be more sustainable, just and appropriate.

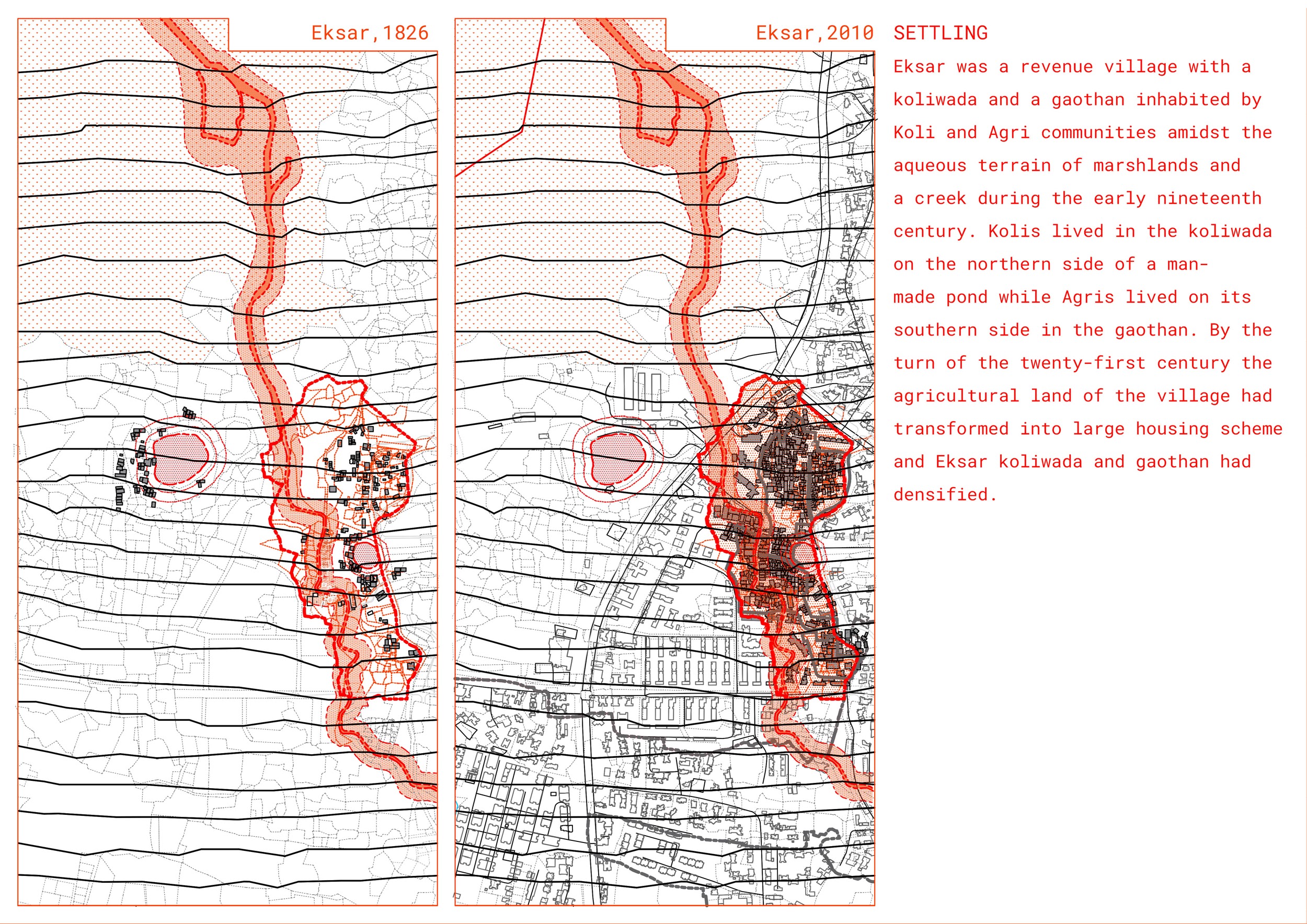

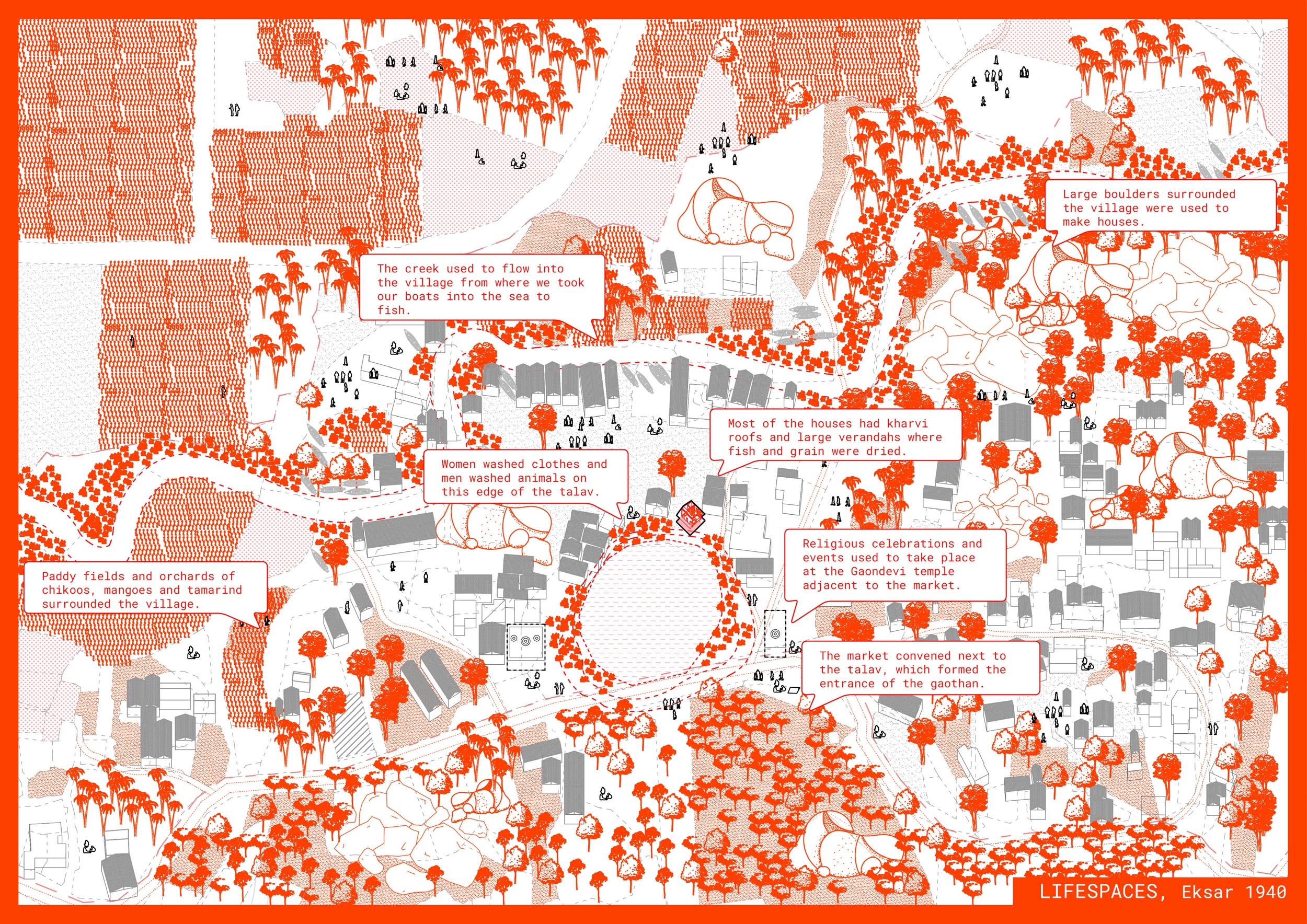

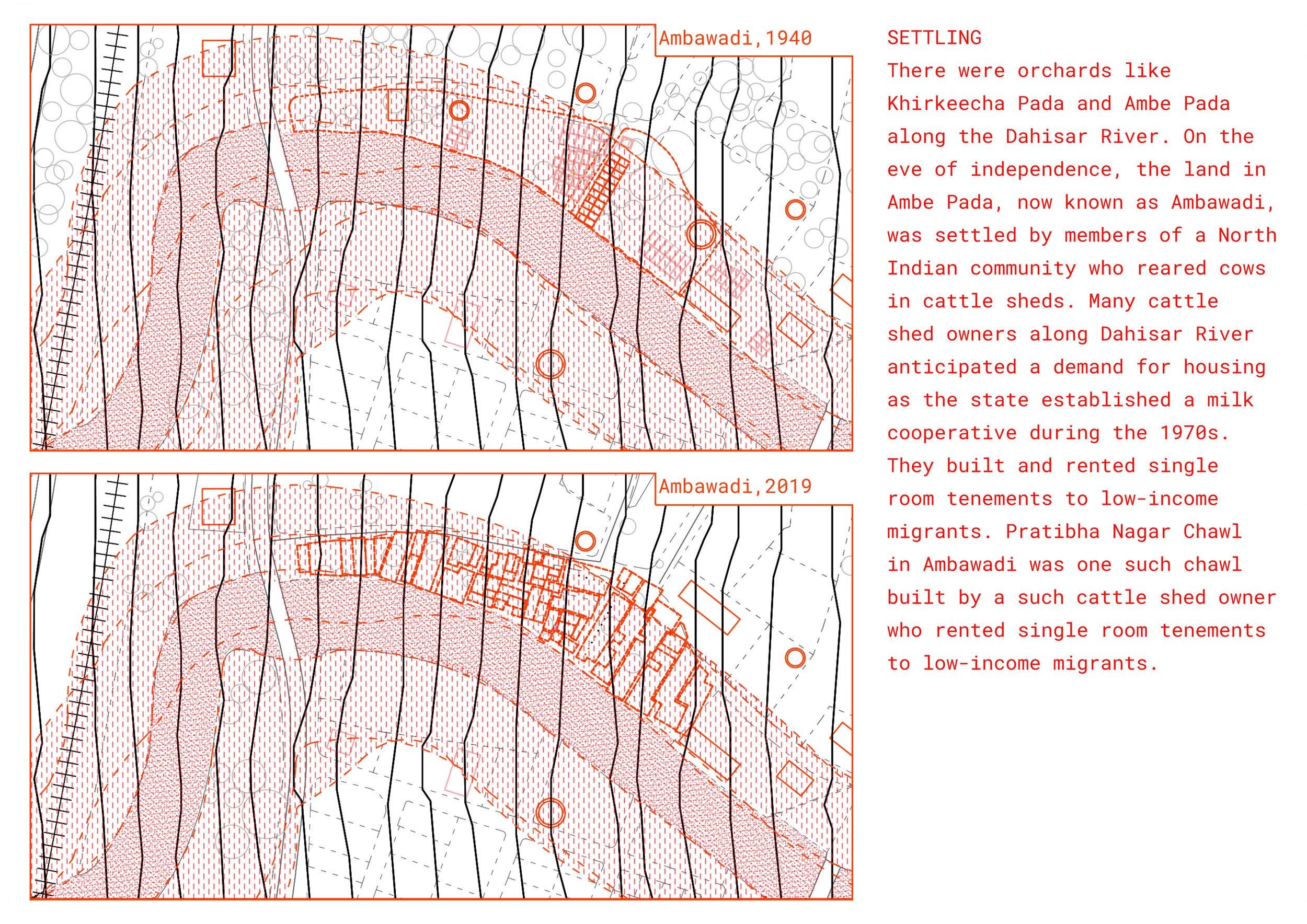

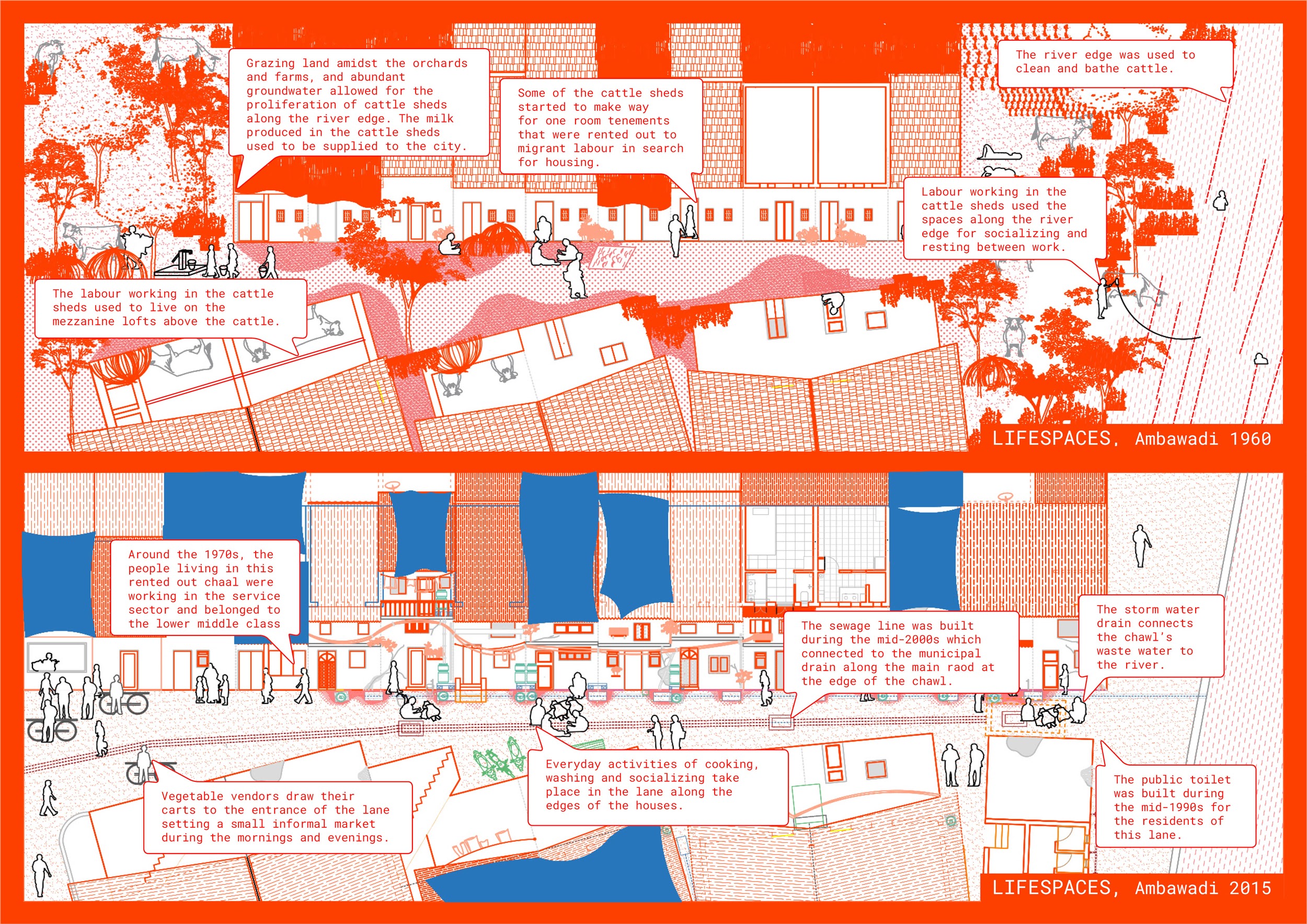

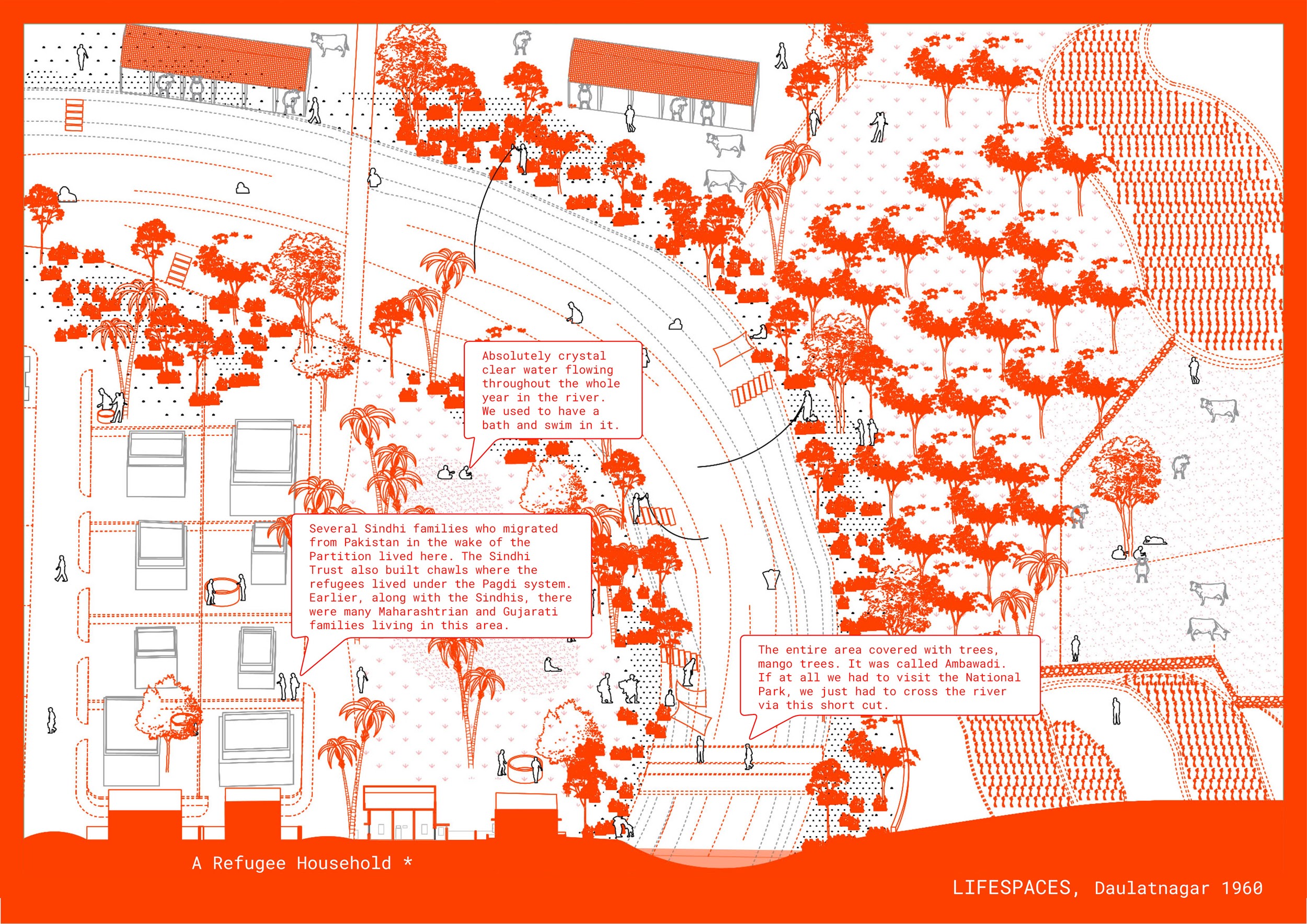

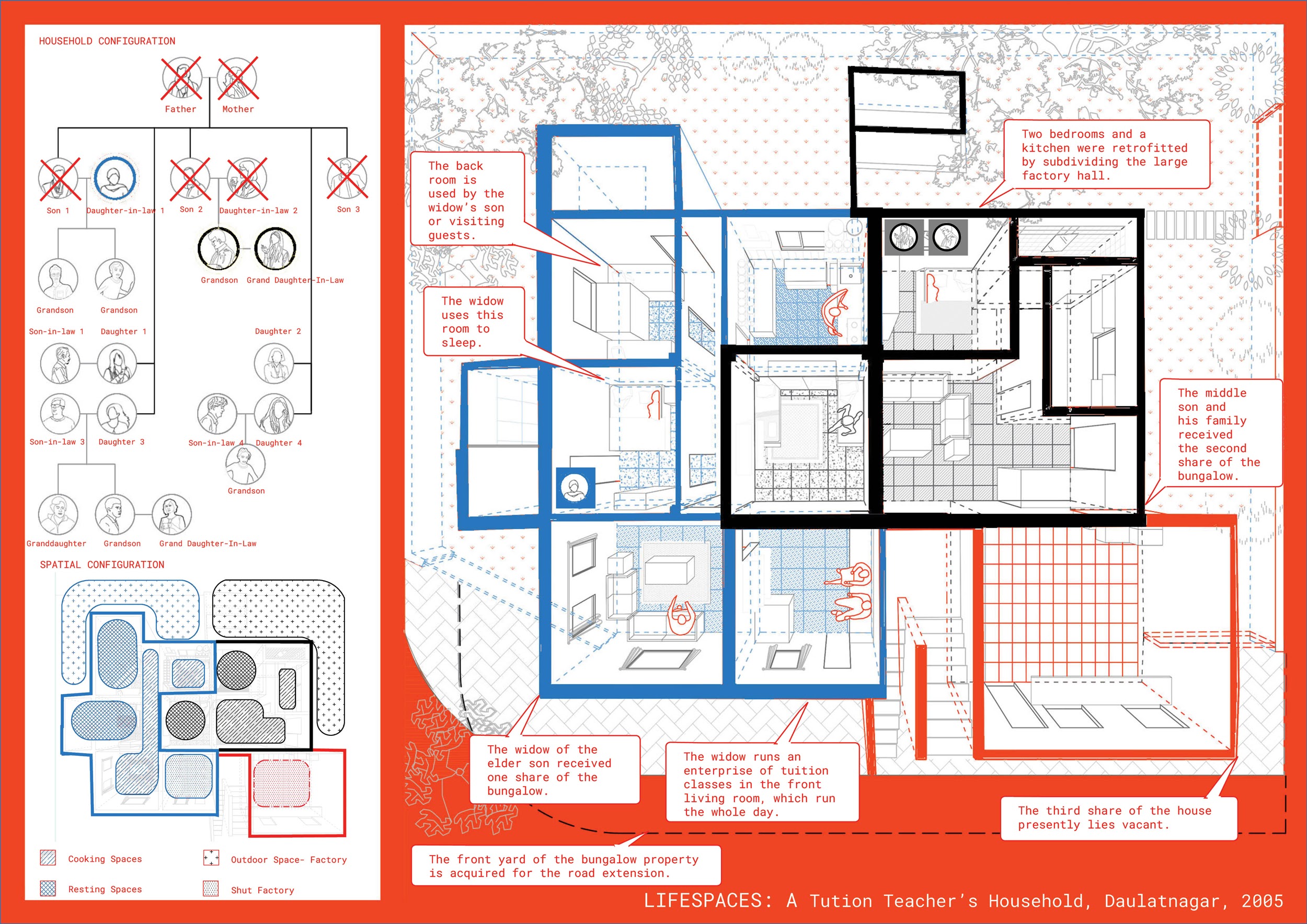

The stories presented in this graphic novel are the outcome of an exploratory phase of inquiry that has focused on arriving at a conceptual and methodological approach to understand such ‘ordinary’ visions and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation. In the course of arriving at conceptually and methodologically, our architectural ethnography unravels fragments of intersection between the ‘biophysical’ and ‘sociopolitical’ histories of place in four localities of the estuarine landscape of Mumbai’s Dahisar River. These fragments are drawn from our ‘deep listening’ to the oral histories of fifteen household experiences, responses and innovations to the everyday monsoonal wetness and its extreme events. We invite the reader to make their own readings of the stories presented in this graphic novel, namely the oral histories of five households amongst the fifteen that we studied.

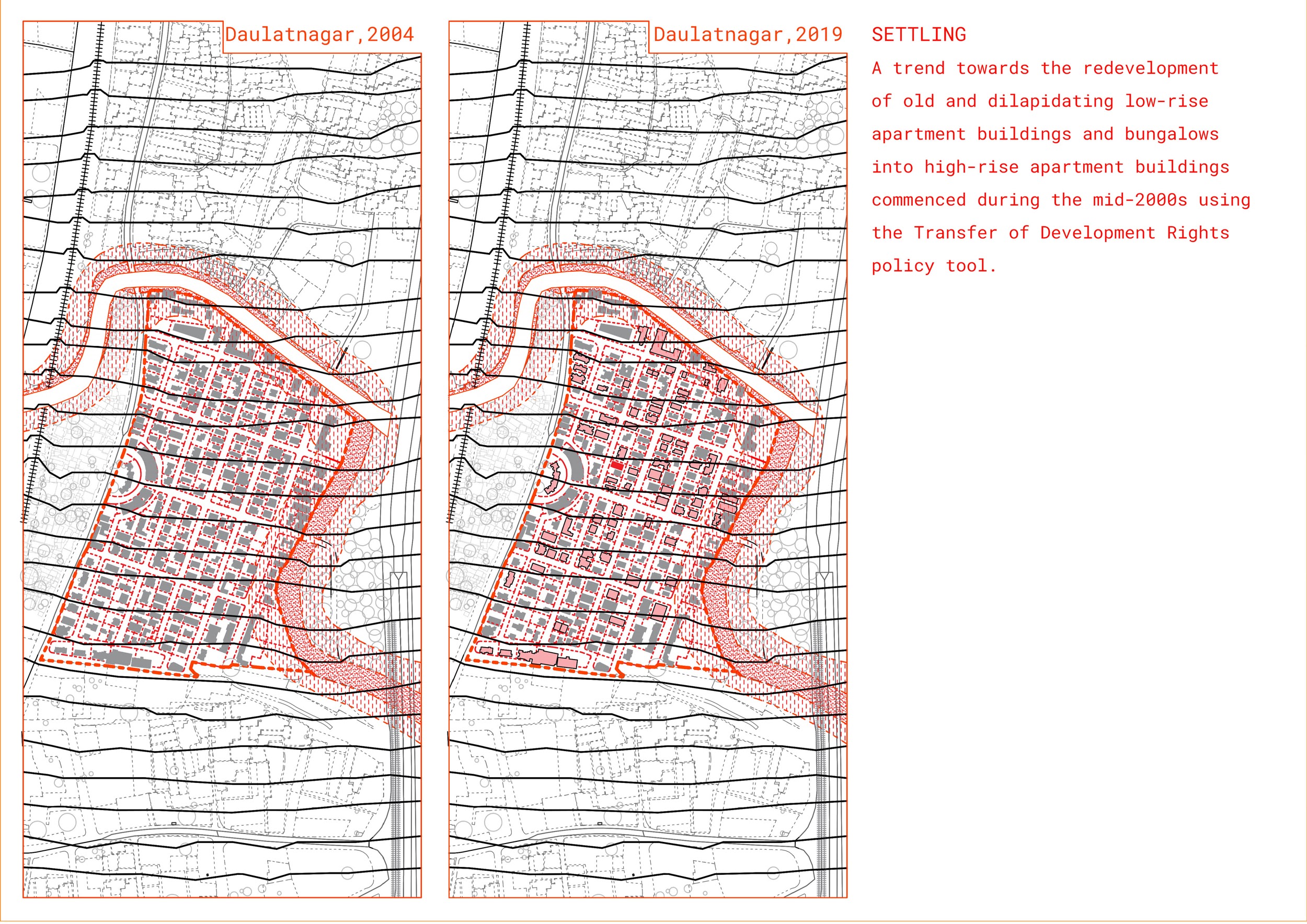

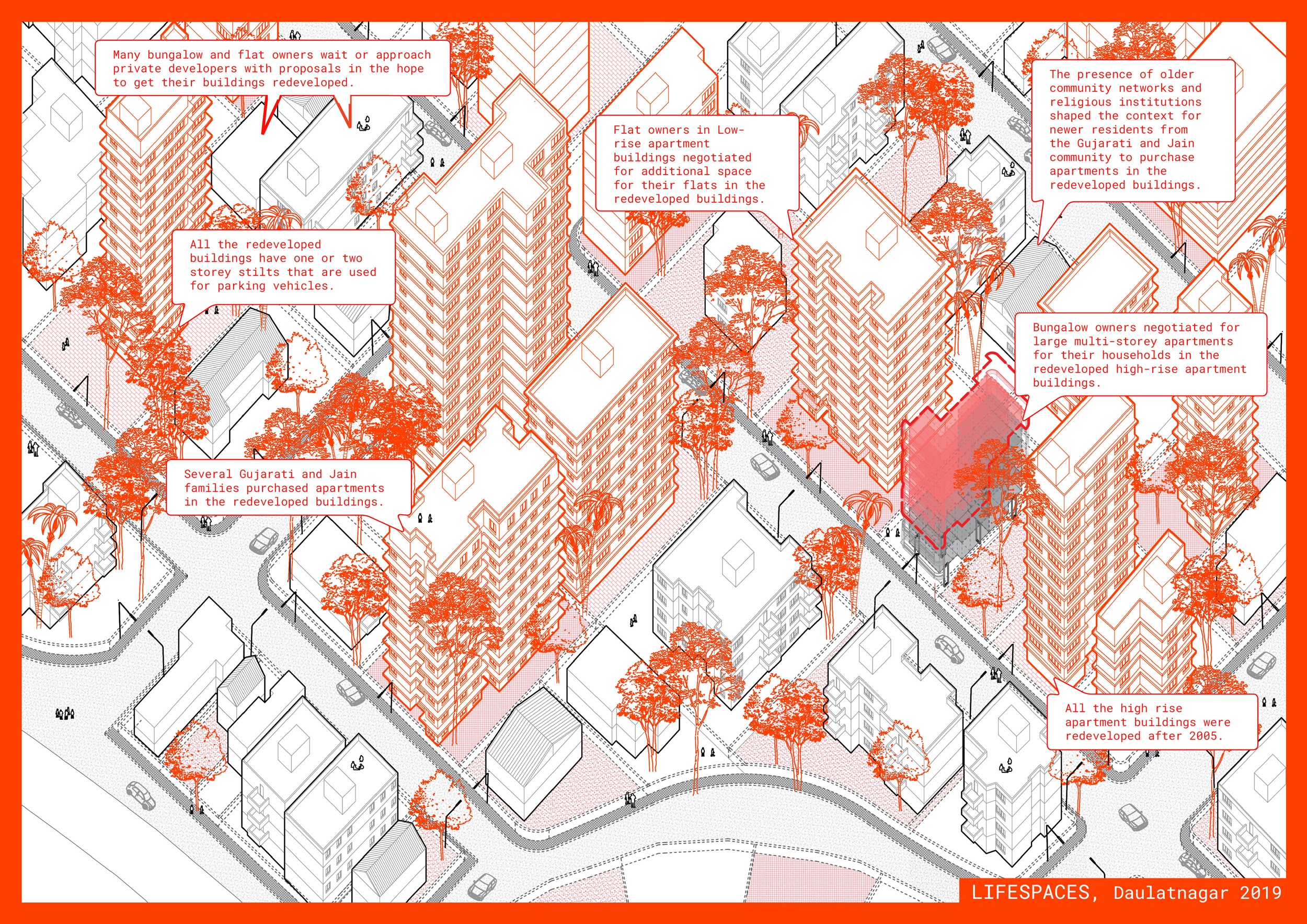

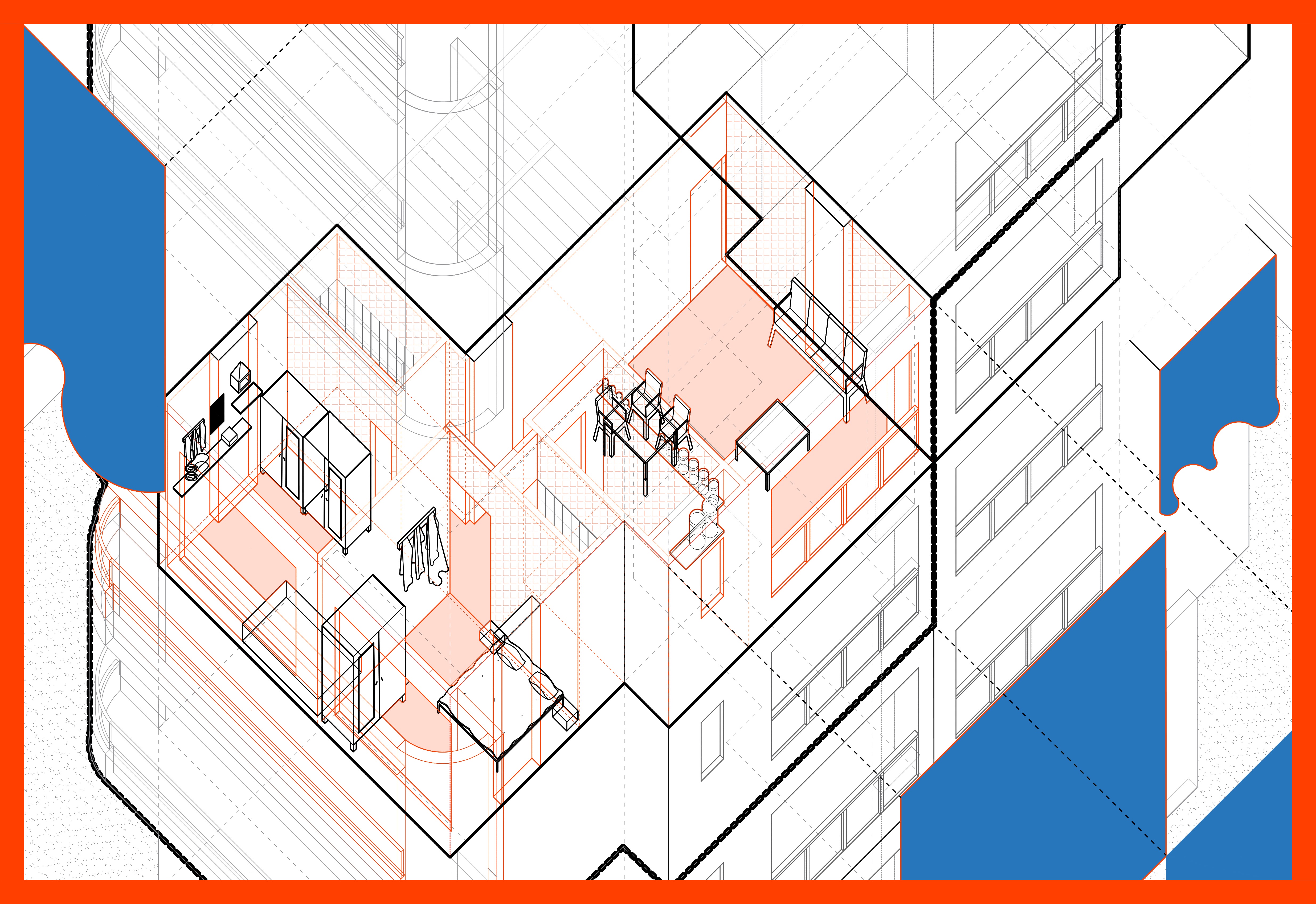

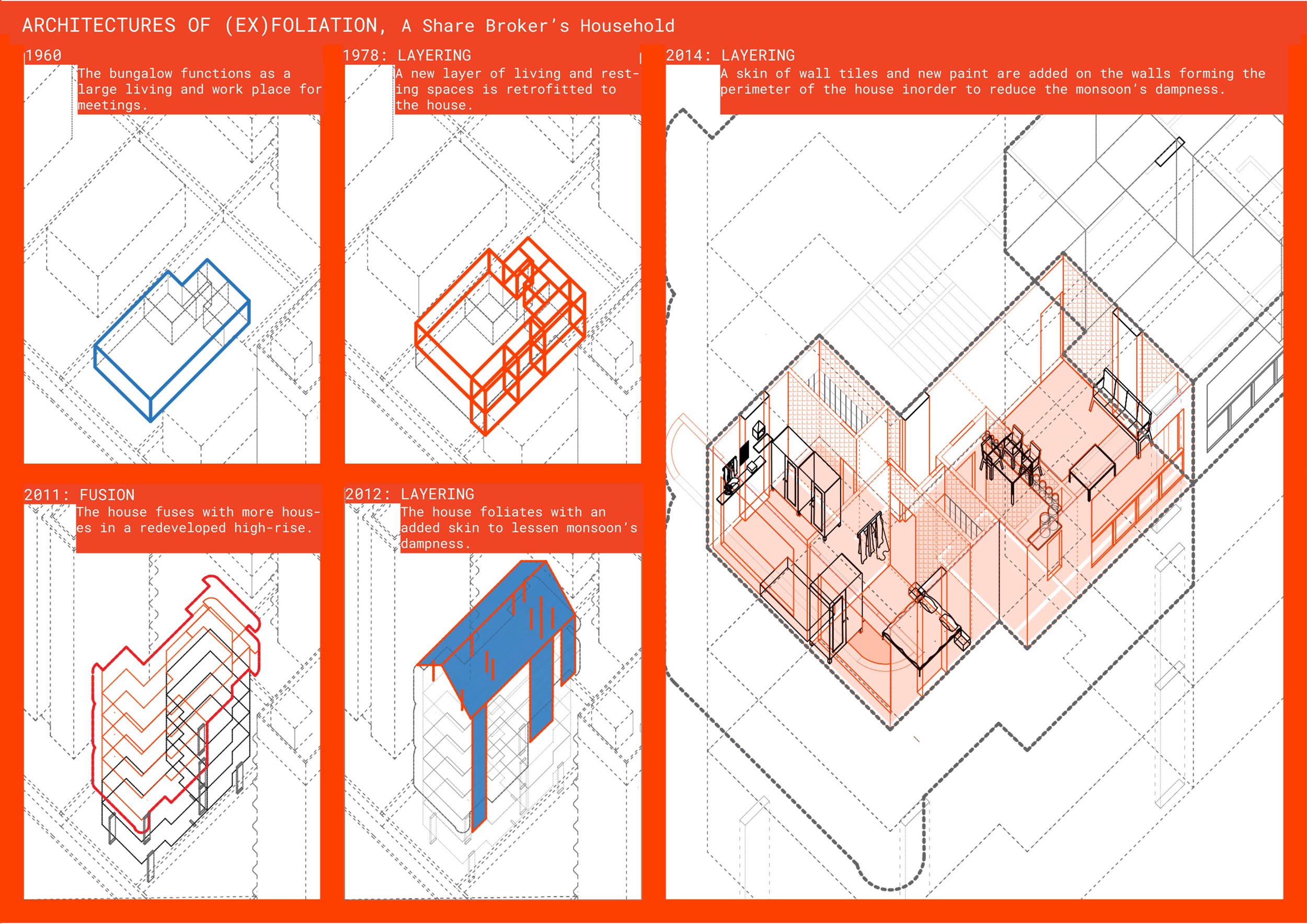

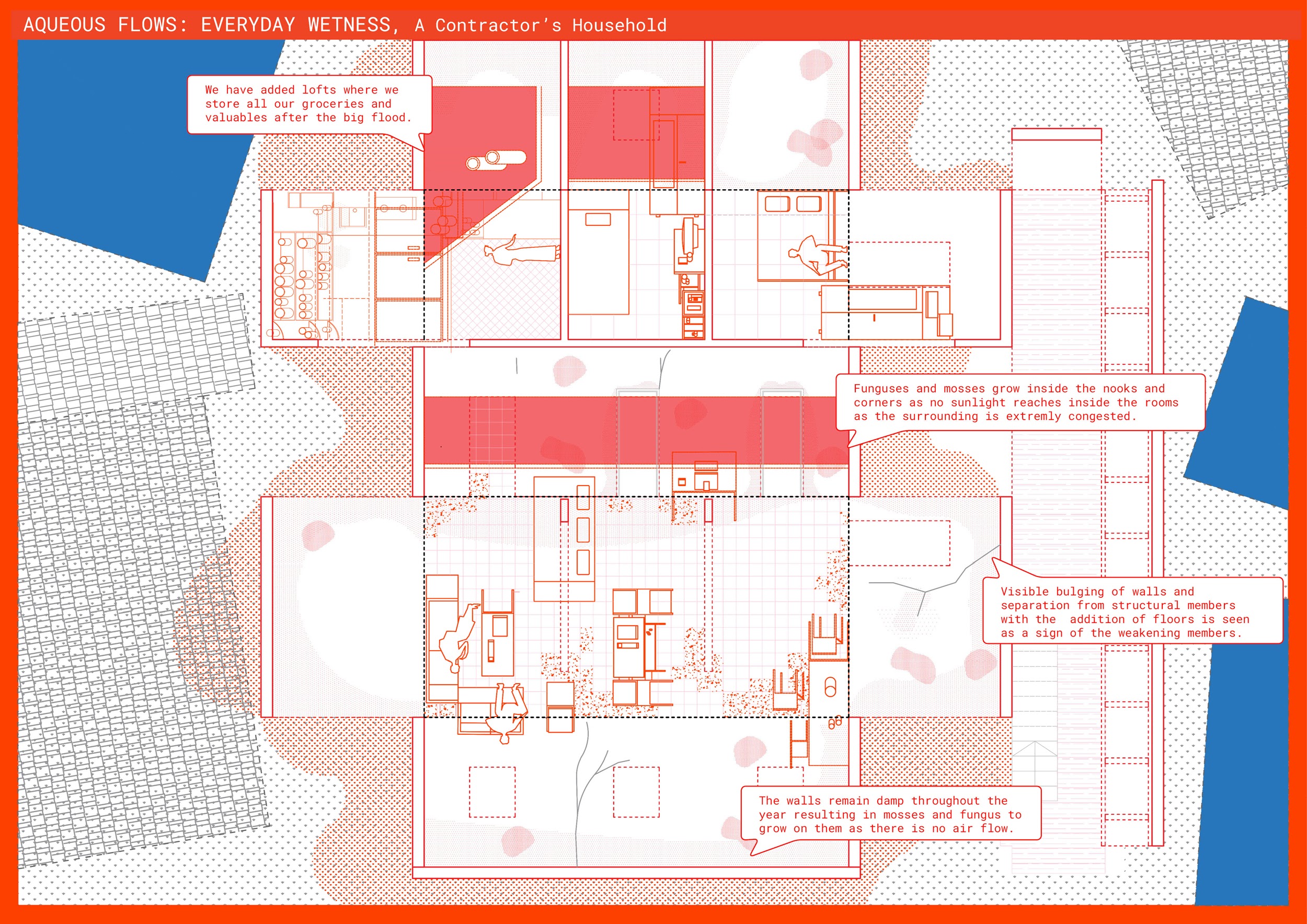

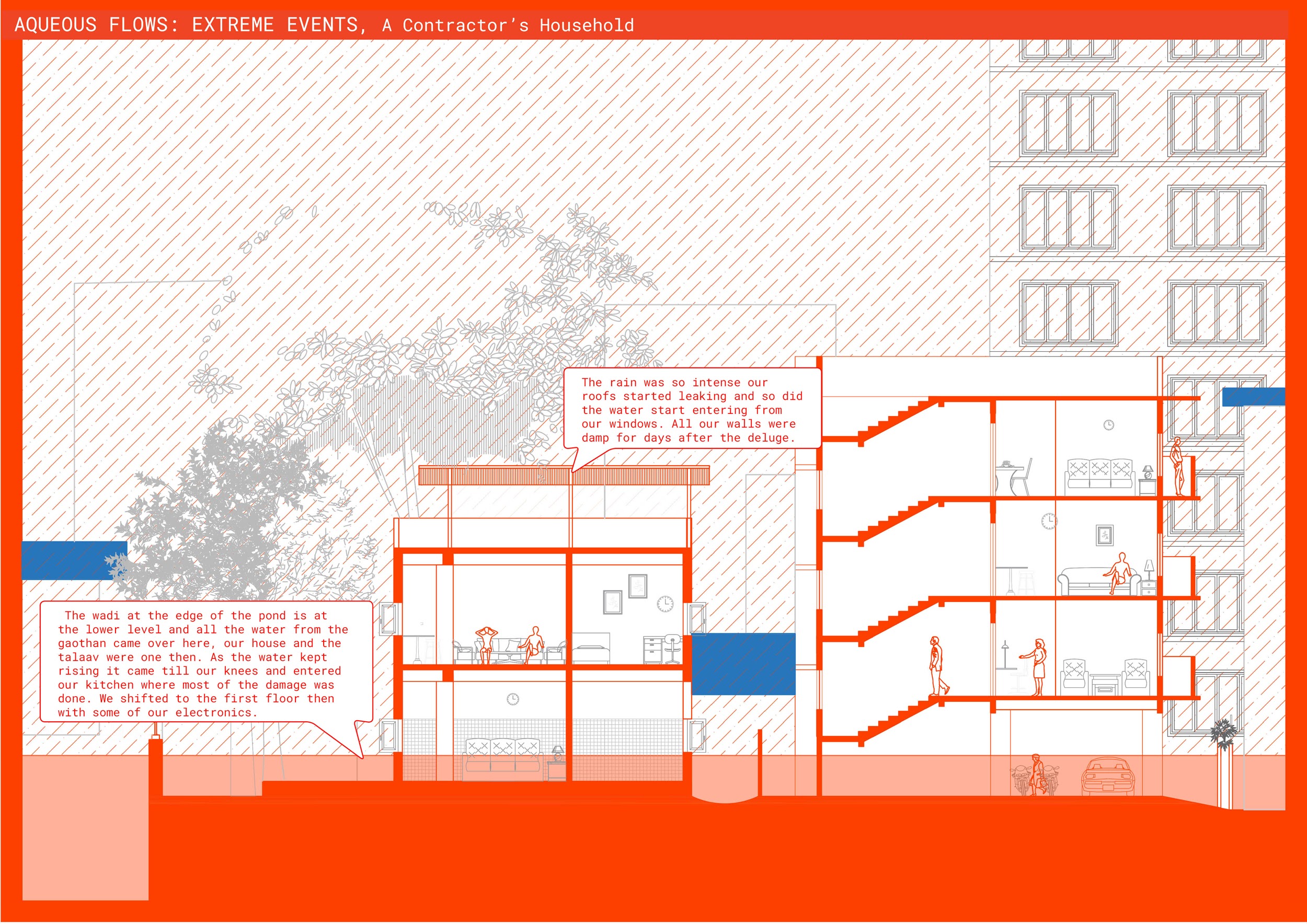

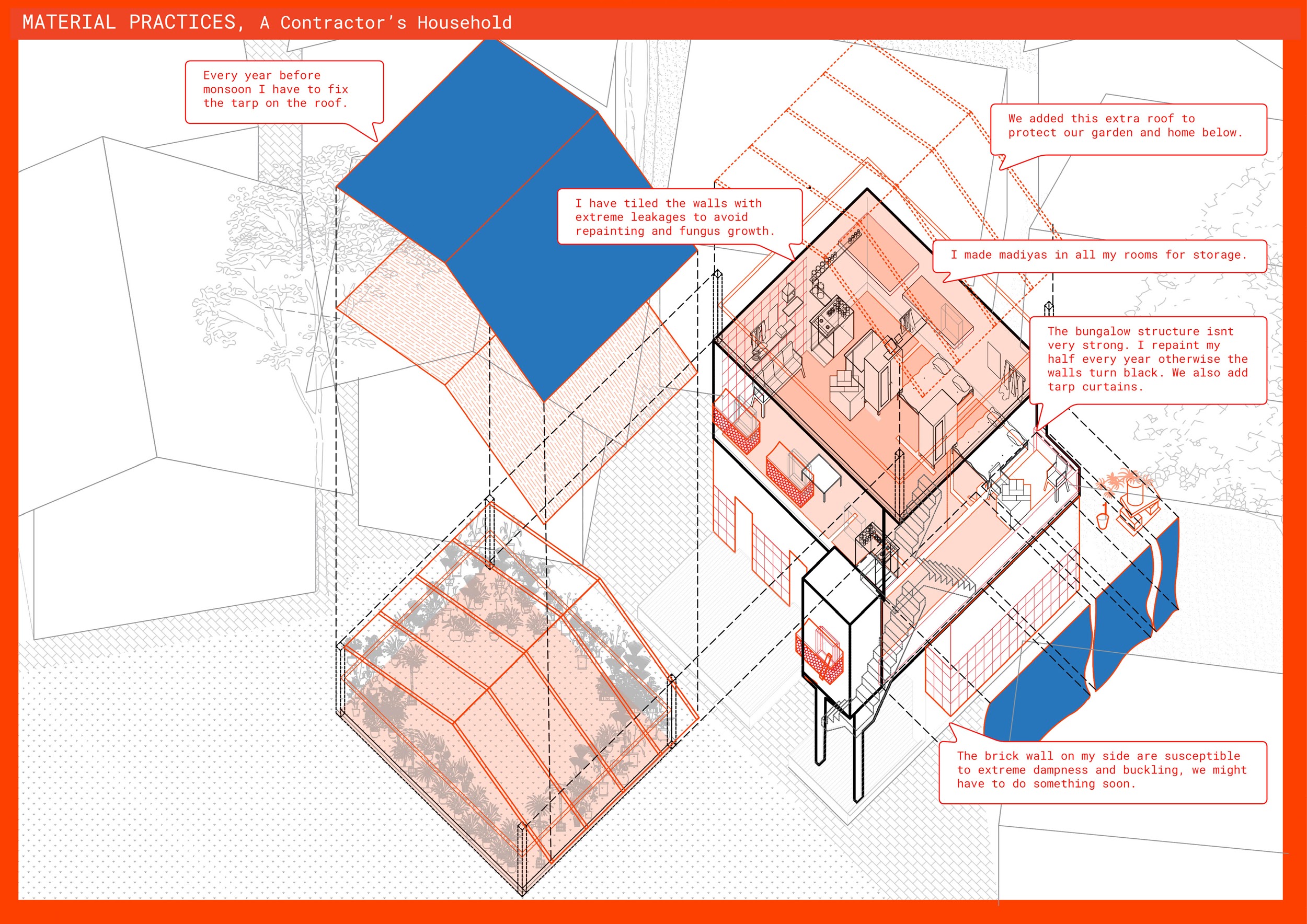

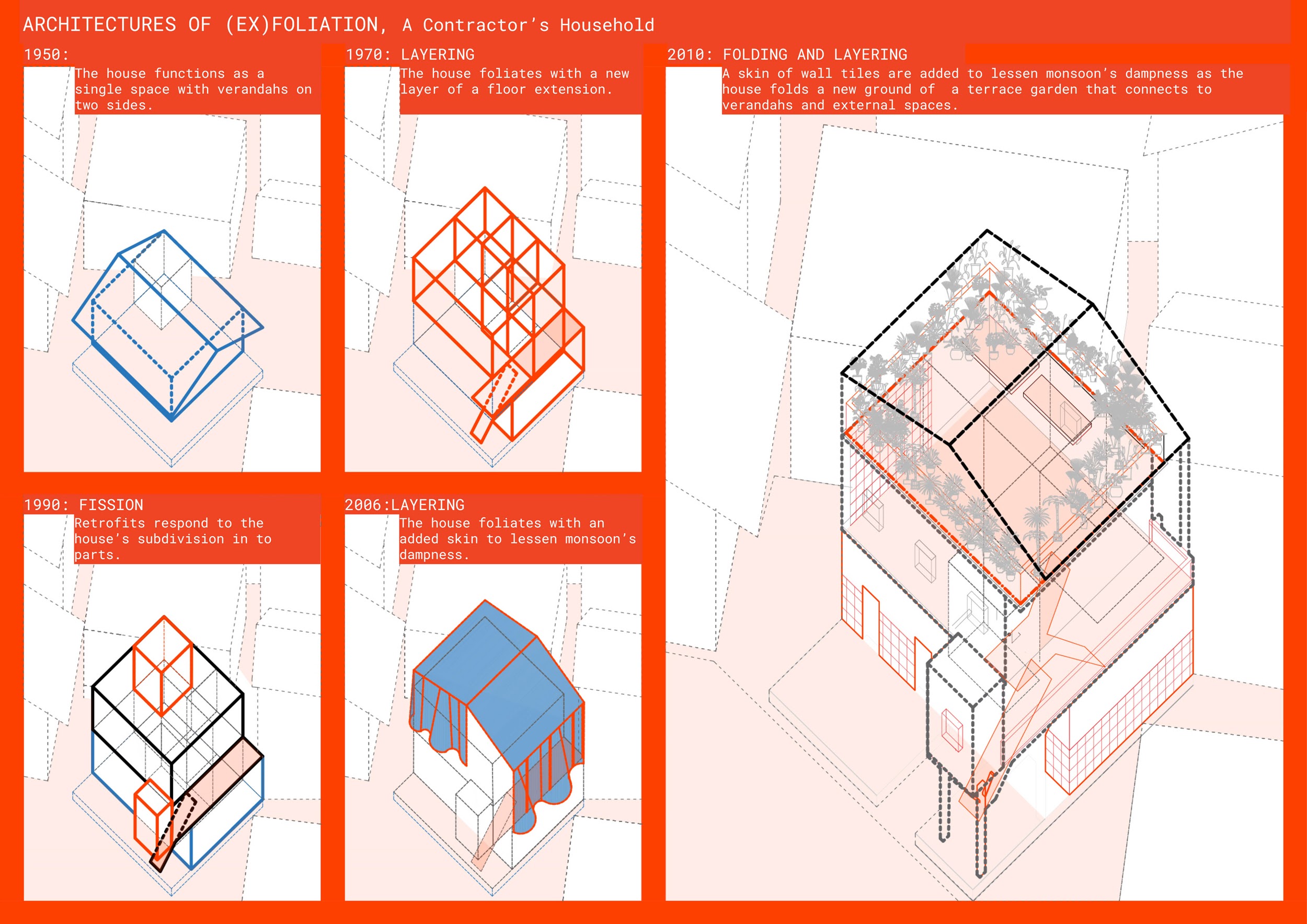

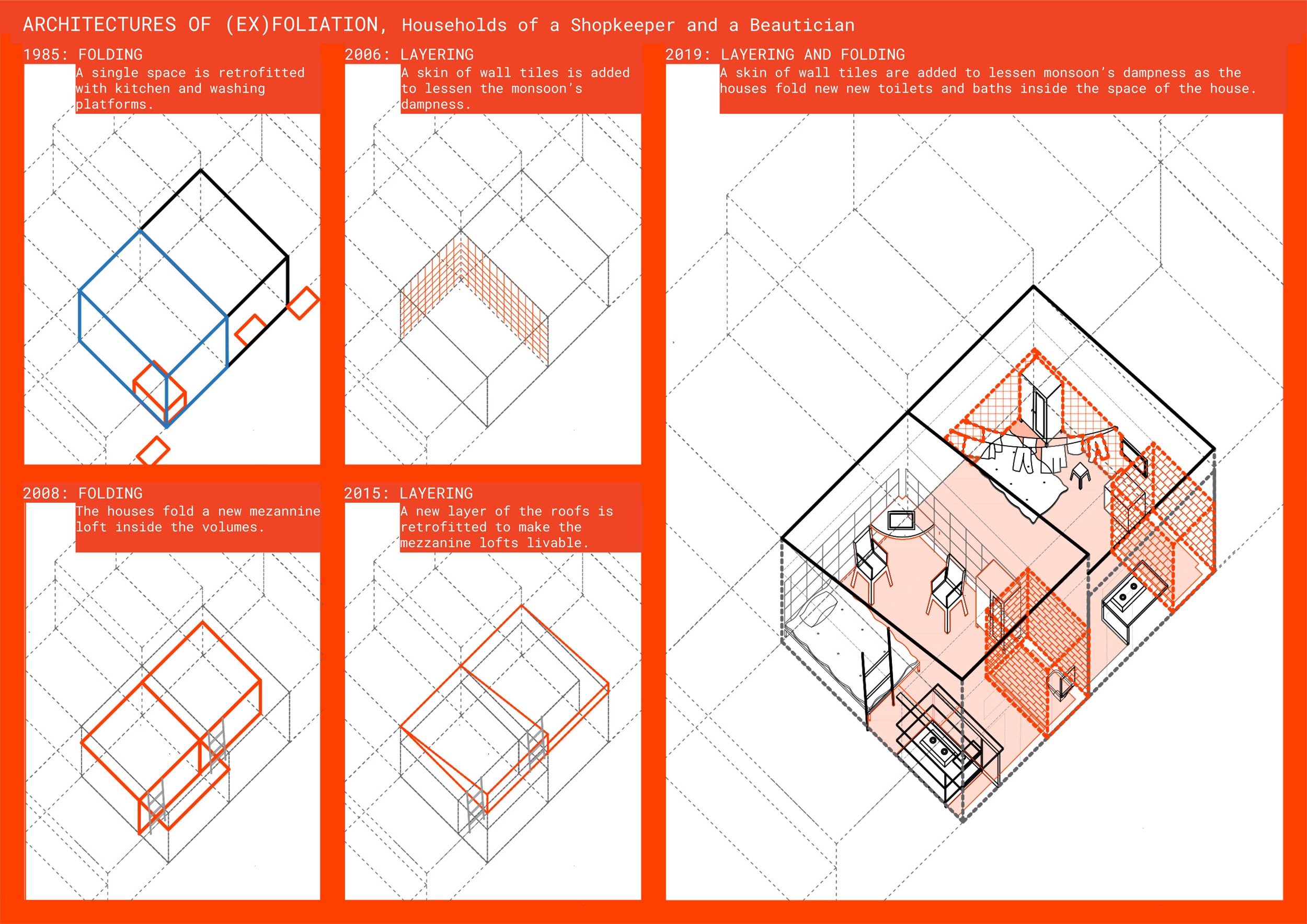

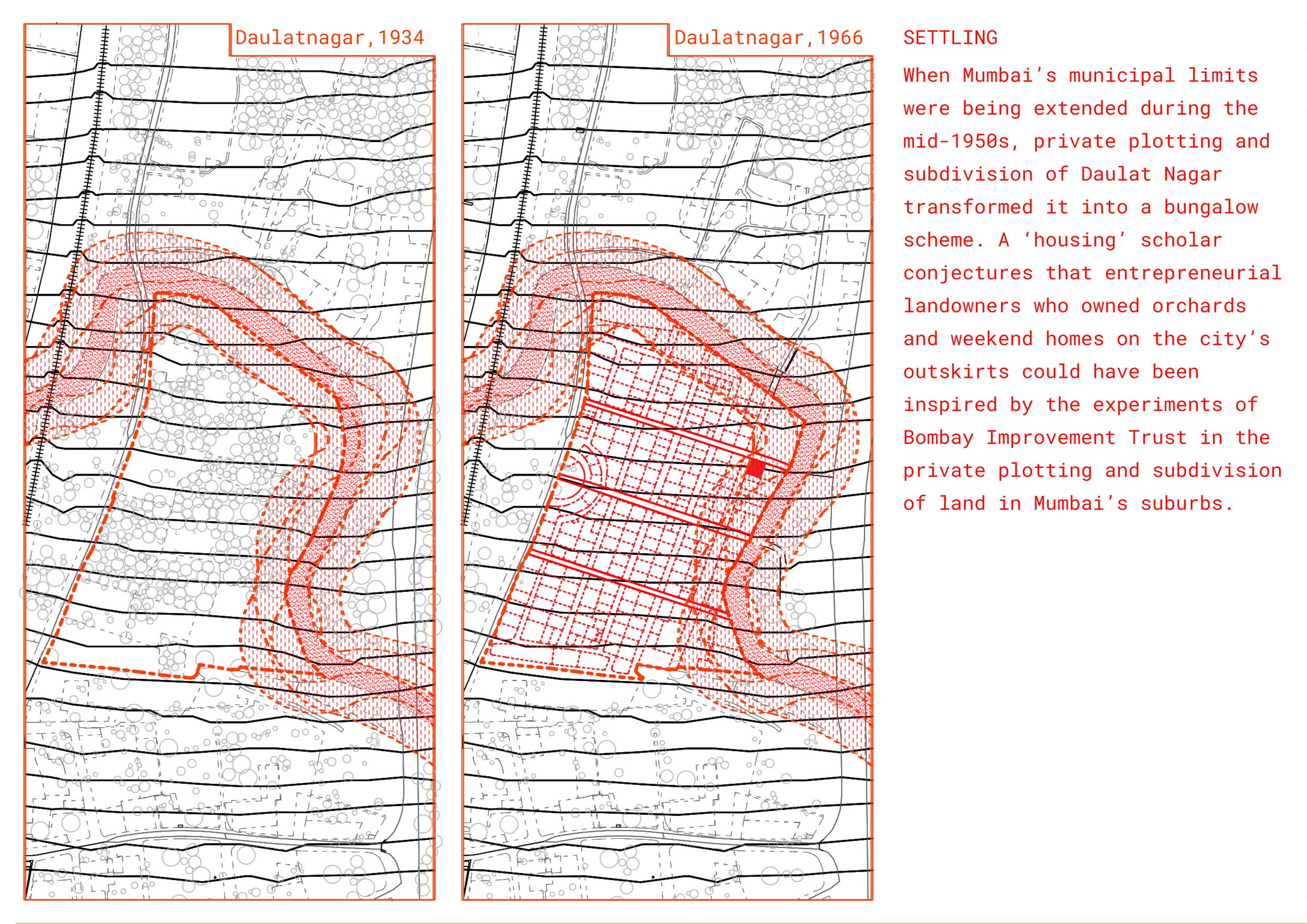

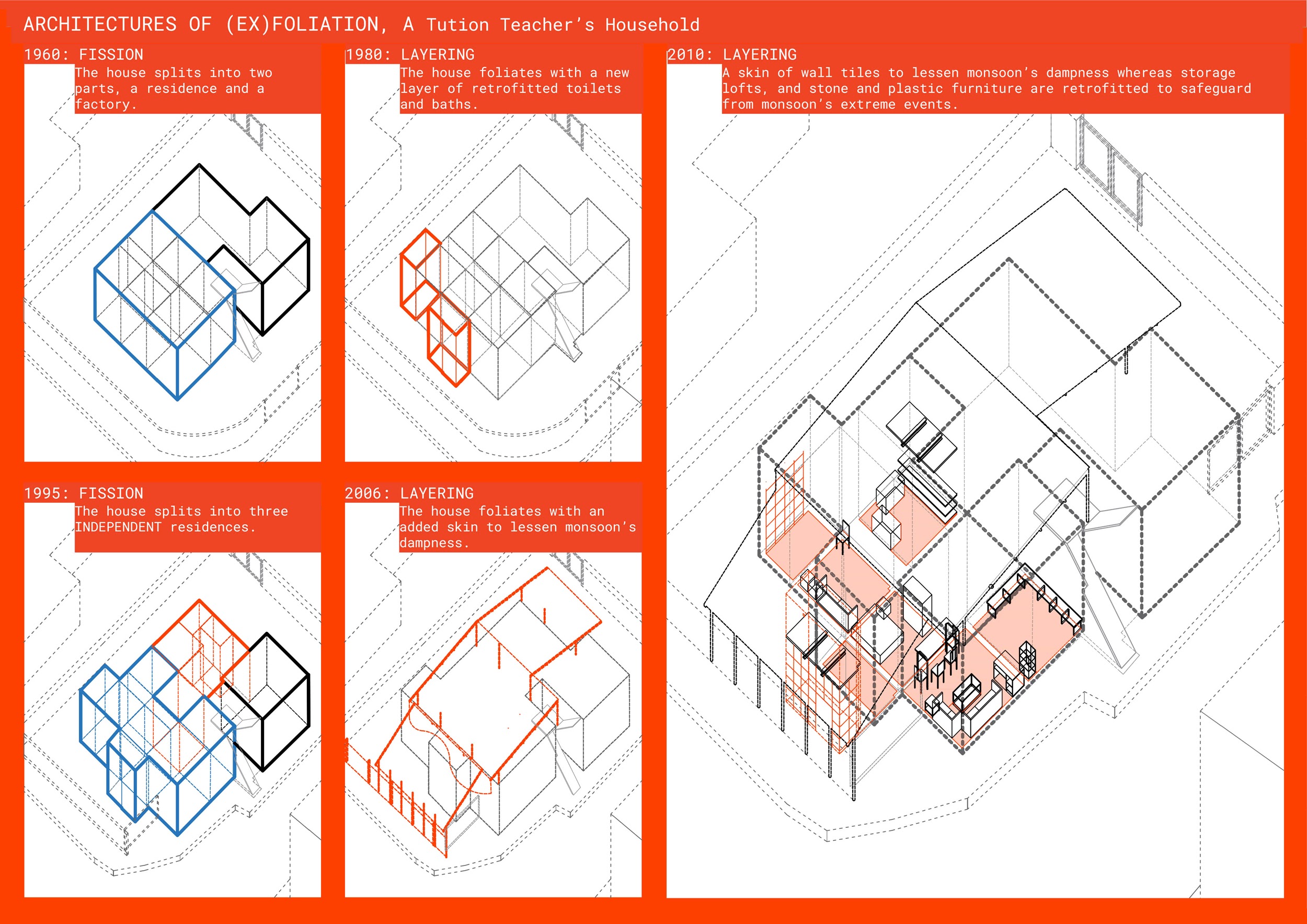

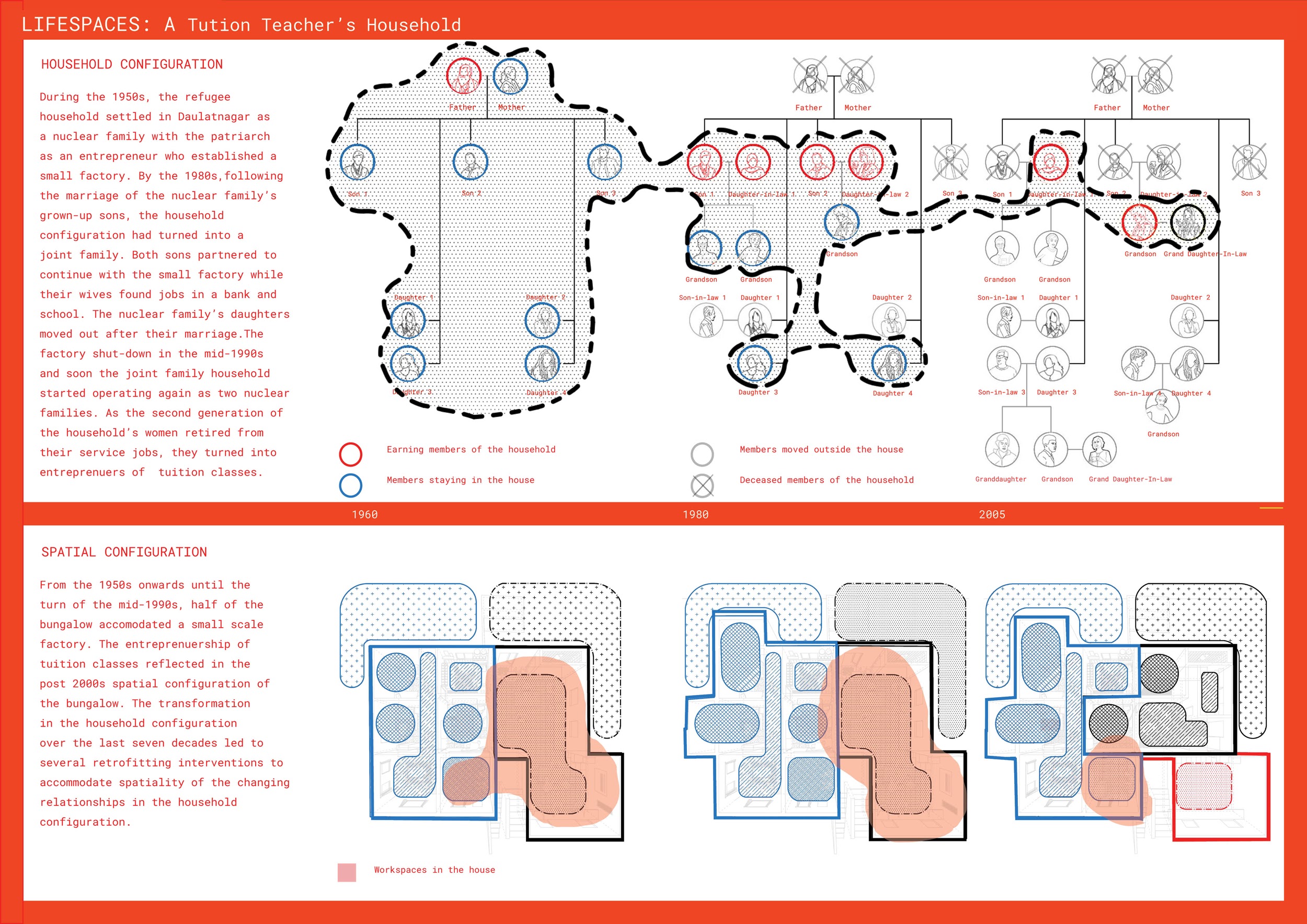

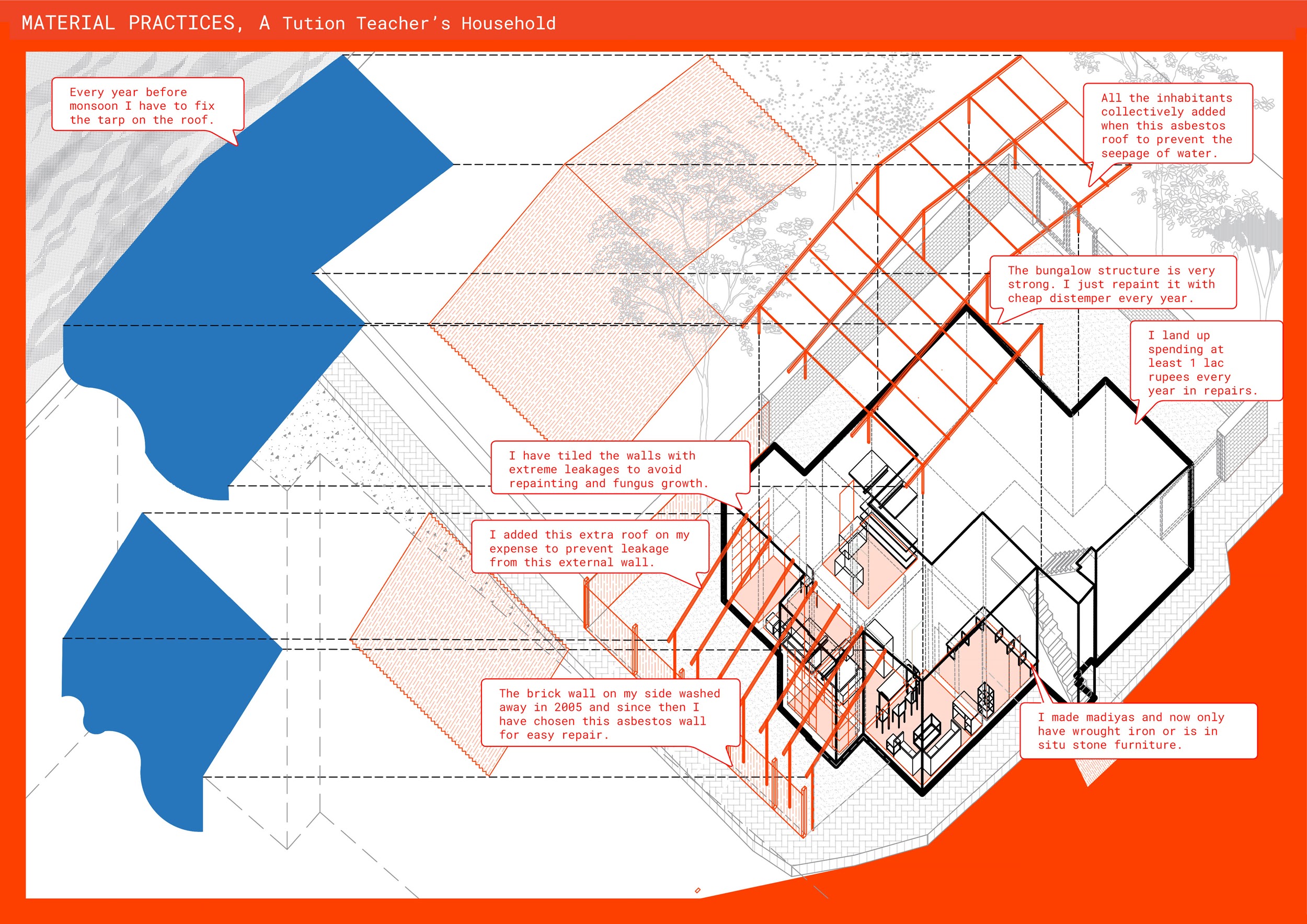

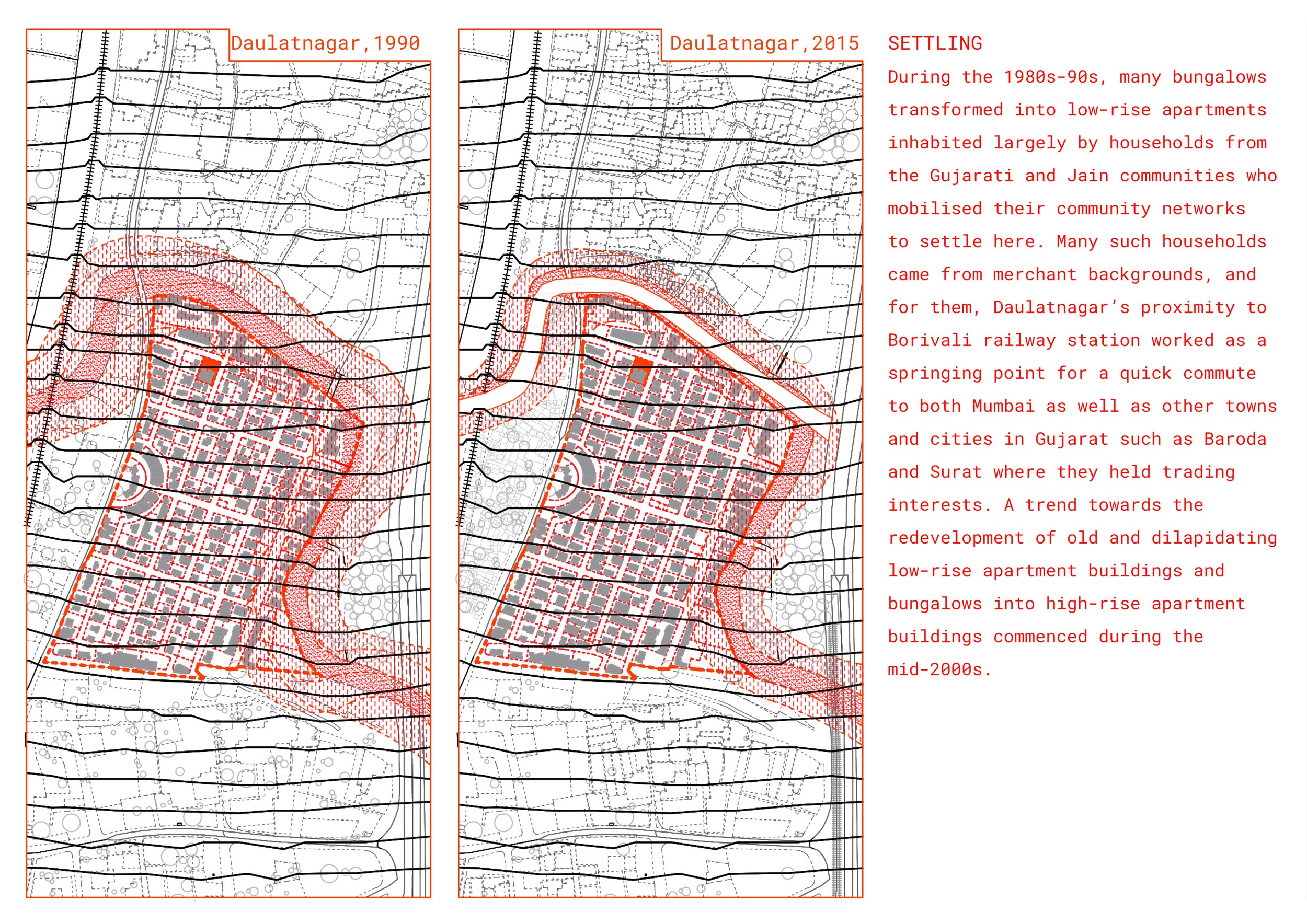

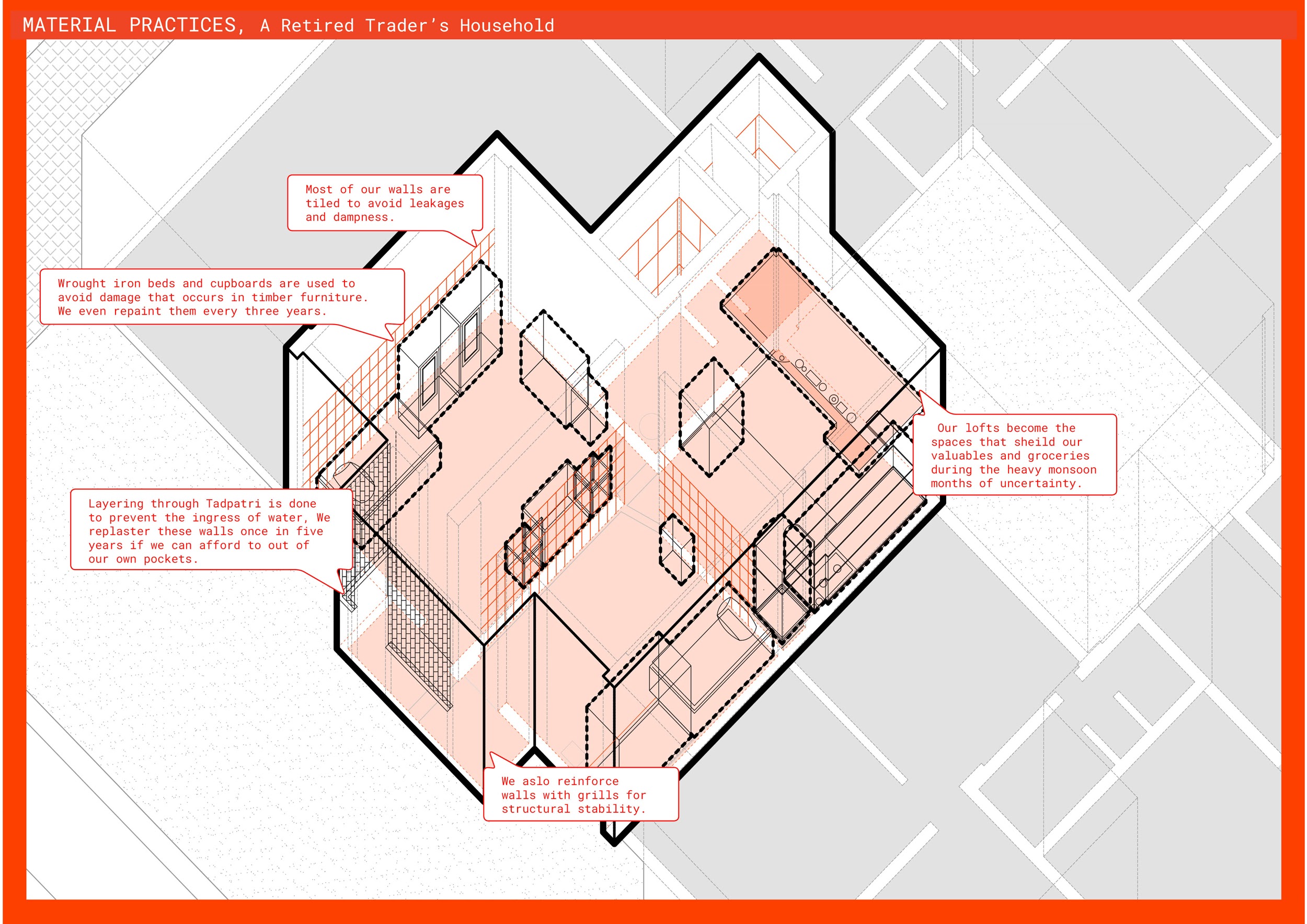

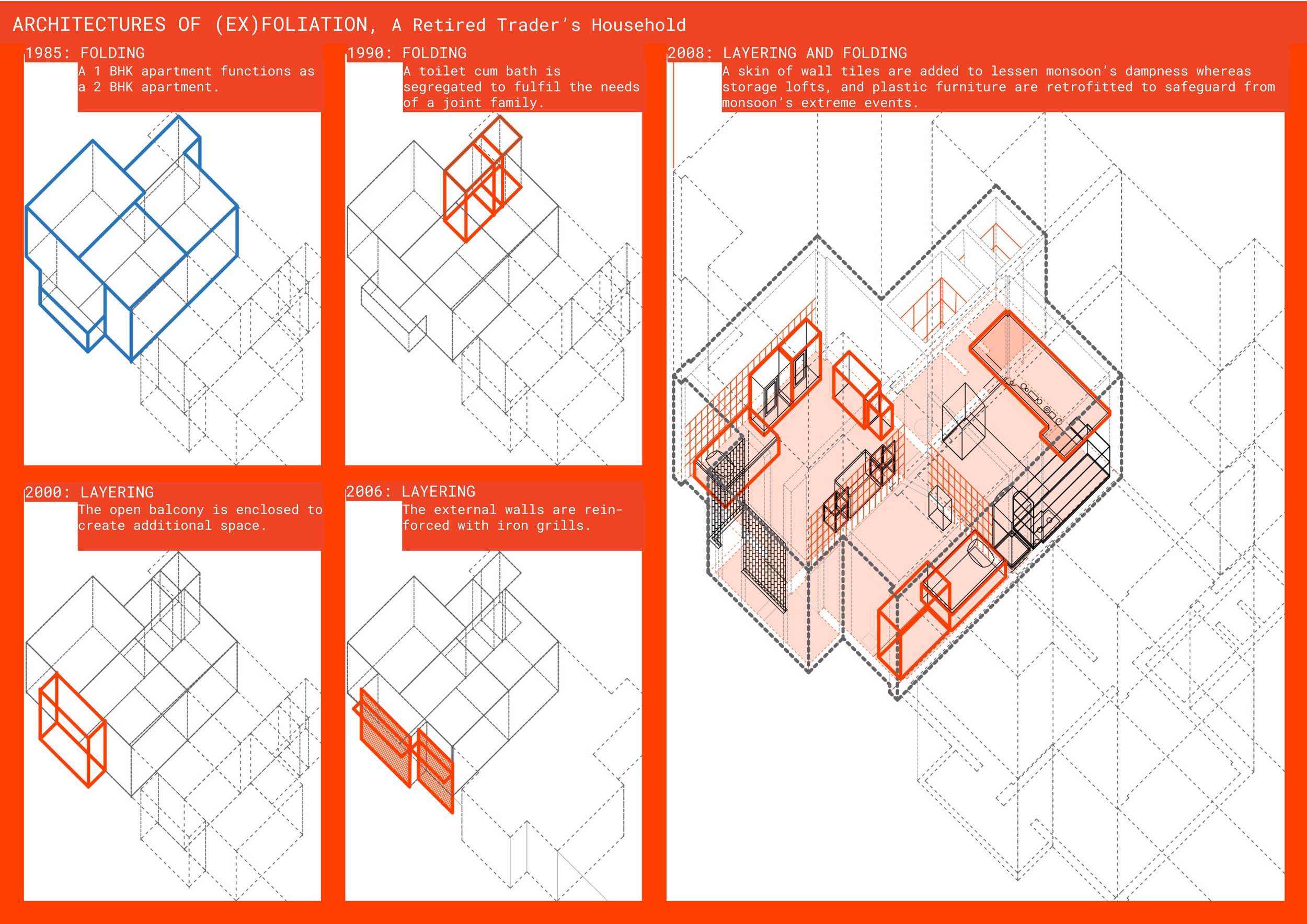

Amongst the many readings possible of the stories that follow, we would like to flag one in this summary that points to our arrival at a conceptual frame. At a time when sponges, forests and swamps have come to grip ontological imaginations of infrastructures as ones that could hold the increasing intensities of in climate changed cities across the world, our focus on the intersection of ‘biophysical’ and ‘sociopolitical’ histories of place draws attention to what we have come to call as the architectures of (ex)foliation. Drawing from our fieldwork in the monsoonal estuary of Dahisar river, architectures of (ex)foliation advances analogies of layering, shedding, folding, fission and fusion to interpret the formal and spatial operations produced by the disjunct forces of settling terrain, life spaces of inhabitants, substance of aqueous flows, and the material practices to adapt landscape and built environment that weave into one another. We contend that democratizing climate action will require active and sustained dialoguing with an ecology of knowledges, including those embedded in the ‘ordinary’ visions and practices that produce architectures of (ex)foliation, to expand what constitutes mitigation and adaptation ‘expertise’ while being responsive to distributional justice in an era of increasing intensities of wetness in climate changed cities.

As everyday monsoonal wetness and its extreme events weave into their life, the protagonist households in this novel aspire to a new, free house on an in-situ elevated ground by tapping into the policy tool of incentivising Floor Space Index to redevelop new housing in the estuarine landscape of Dahisar River. However, not every household aspiration to find home in such a new house is fulfilled as their opportunities are compounded by court cases over property rights, long bureaucratic processes to acquire land or building titles, India’s demonetization initiative, limitations imposed by Maharashtra’s new initiative to regulate real estate, and now even the pandemic. Even those whose aspirations to find a new, free house on an in-situ elevated ground are fulfilled have to find ways to endure the ever present cyclical wetness in a monsoonal estuary. In this meantime, architectures of (ex)foliation come to make old and new builtform resilient to monsoon’s everyday wetness and its extreme events with all their potentials and shortcomings.

We thus offer architectures of (ex)foliation as a heuristic frame to inquire into the myriad ways in which monsoonal wetness weaves into urban life and engage with possibilities to democratize climate action. We hope that climate action practitioners could find this heuristic frame of relevance to develop a critical engagement with the spatialities of habitation while finding ways to collaborate with an ecology of knowledges embedded in ordinary ‘visions’ and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation.

We arrived at architectures of (ex)foliation in the process of asking little questions of the material from the oral histories that we had collected while engaging the translation of our analysis in drawings. Three months into this seven month long study which began in mid-December 2019, we were gripped in a life altering global pandemic. Sitting in our homes across two cities and conversing across an online platform, we collaboratively tried to figure out how to “draw” wetness in the weave of life from the copious notes, interview transcripts, and limited fieldwork sketches and photographs that we had put together in the first three months of the study. The drawings in this novel are full of our struggle to draw monsoonal wetness in the weave of life, one which we hope to address in a future work.

Abhijit Ekbote, Dipti Talpade, Vinisha Kuckian and Megha Dumasya - a big thank you for extending a helping hand to acquaint us with many of our field interlocutors in the four neighbourhoods that we chose to study, and always being there to answer our odd queries. We are grateful to all the members of the fifteen households who invited us into their homes and lives during the course of our research to produce this novel. Deep conversations with you not only helped us make sense of our collective lives but also helped frame, what we have now come to consider as, the right question to be asked with regards to climate action. We humbly thank you for being our guides whilst hoping that our work may eventually engender the intellectual resources necessary to make a difference to life in Mumbai’s inhabited sea.

This project received financial support from the Society for Environment and Architecture, Mumbai, and the University of Pennsylvania Institute for the Advanced Study of India for The Inhabited Sea collaboration. Our work owes much to the thoughtful suggestions of colleagues with whom we delved collectively in The Inhabited Sea of stimulating conversations over several workshops. We hope that you will be able to recognize your contributions in the stories that follow. Nikhil Anand and Lalitha Kamath, we cannot thank you enough for nurturing our work in conversations with you beyond the life of The Inhabited Sea collaboration. Finally, we would like to dedicate this novel to the efforts our commune at the School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) - our colleagues, trustees, research fellows, students - for co-shaping SEA as our vibrant intellectual home, asking tough questions of this work, nurturing it with care and always rooting for us; one could not ask for more.

In the backdrop of a gathering storm of changing weather and rising seas, the current conversation on Mumbai’s future sketches extreme ends of a teleological future. The protagonists of this conversation have delved on four kinds of actions in response to sea-level rise projections for 2050: first, infrastructures in the form of widening water courses and constructing tall, concrete retaining walls along their edges to drain monsoonal waters away from land; second, “slum” demolitions along water courses to increase capacities for draining monsoonal waters; third, enmasse city relocation and resettlement on a higher ground; and fourth, post-apocalypse scenarios of a submerged city for leisure activities. Such a conversation attempts to futureproof the city for a post-weather tipping point but, in the process, weakens and even dislocates the claims of majority households in the present. Moreover, the imaginations of infrastructures in these conversations, largely predicated on containing water and making the city dry, actually end up making the city either more vulnerable to “natural” disasters or shift the existing problems elsewhere.

It thus comes as no surprise that some scholars have begun to call upon Mumbai’s residents and leaders alike to demand for a climate action plan that is not only ambitious and imaginative but also just. But, in the meantime, how do majority households experience, respond to and innovate in the process of inhabiting monsoon’s everyday wetness and its extreme events in Mumbai?

Despite environmental improvement efforts that have often harmed them, a majority of households are engaged in a series of practices and measures to live with wetness, and adapt to climate and ecological uncertainty in Mumbai. Spatial thinking has remained severely limited in understanding and engaging these ‘ordinary’ visions and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation that are likely to be more sustainable, just and appropriate.

The stories presented in this graphic novel are the outcome of an exploratory phase of inquiry that has focused on arriving at a conceptual and methodological approach to understand such ‘ordinary’ visions and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation. In the course of arriving at conceptually and methodologically, our architectural ethnography unravels fragments of intersection between the ‘biophysical’ and ‘sociopolitical’ histories of place in four localities of the estuarine landscape of Mumbai’s Dahisar River. These fragments are drawn from our ‘deep listening’ to the oral histories of fifteen household experiences, responses and innovations to the everyday monsoonal wetness and its extreme events. We invite the reader to make their own readings of the stories presented in this graphic novel, namely the oral histories of five households amongst the fifteen that we studied.

Amongst the many readings possible of the stories that follow, we would like to flag one in this summary that points to our arrival at a conceptual frame. At a time when sponges, forests and swamps have come to grip ontological imaginations of infrastructures as ones that could hold the increasing intensities of in climate changed cities across the world, our focus on the intersection of ‘biophysical’ and ‘sociopolitical’ histories of place draws attention to what we have come to call as the architectures of (ex)foliation. Drawing from our fieldwork in the monsoonal estuary of Dahisar river, architectures of (ex)foliation advances analogies of layering, shedding, folding, fission and fusion to interpret the formal and spatial operations produced by the disjunct forces of settling terrain, life spaces of inhabitants, substance of aqueous flows, and the material practices to adapt landscape and built environment that weave into one another. We contend that democratizing climate action will require active and sustained dialoguing with an ecology of knowledges, including those embedded in the ‘ordinary’ visions and practices that produce architectures of (ex)foliation, to expand what constitutes mitigation and adaptation ‘expertise’ while being responsive to distributional justice in an era of increasing intensities of wetness in climate changed cities.

As everyday monsoonal wetness and its extreme events weave into their life, the protagonist households in this novel aspire to a new, free house on an in-situ elevated ground by tapping into the policy tool of incentivising Floor Space Index to redevelop new housing in the estuarine landscape of Dahisar River. However, not every household aspiration to find home in such a new house is fulfilled as their opportunities are compounded by court cases over property rights, long bureaucratic processes to acquire land or building titles, India’s demonetization initiative, limitations imposed by Maharashtra’s new initiative to regulate real estate, and now even the pandemic. Even those whose aspirations to find a new, free house on an in-situ elevated ground are fulfilled have to find ways to endure the ever present cyclical wetness in a monsoonal estuary. In this meantime, architectures of (ex)foliation come to make old and new builtform resilient to monsoon’s everyday wetness and its extreme events with all their potentials and shortcomings.

We thus offer architectures of (ex)foliation as a heuristic frame to inquire into the myriad ways in which monsoonal wetness weaves into urban life and engage with possibilities to democratize climate action. We hope that climate action practitioners could find this heuristic frame of relevance to develop a critical engagement with the spatialities of habitation while finding ways to collaborate with an ecology of knowledges embedded in ordinary ‘visions’ and practices of climate mitigation and adaptation.

We arrived at architectures of (ex)foliation in the process of asking little questions of the material from the oral histories that we had collected while engaging the translation of our analysis in drawings. Three months into this seven month long study which began in mid-December 2019, we were gripped in a life altering global pandemic. Sitting in our homes across two cities and conversing across an online platform, we collaboratively tried to figure out how to “draw” wetness in the weave of life from the copious notes, interview transcripts, and limited fieldwork sketches and photographs that we had put together in the first three months of the study. The drawings in this novel are full of our struggle to draw monsoonal wetness in the weave of life, one which we hope to address in a future work.

Abhijit Ekbote, Dipti Talpade, Vinisha Kuckian and Megha Dumasya - a big thank you for extending a helping hand to acquaint us with many of our field interlocutors in the four neighbourhoods that we chose to study, and always being there to answer our odd queries. We are grateful to all the members of the fifteen households who invited us into their homes and lives during the course of our research to produce this novel. Deep conversations with you not only helped us make sense of our collective lives but also helped frame, what we have now come to consider as, the right question to be asked with regards to climate action. We humbly thank you for being our guides whilst hoping that our work may eventually engender the intellectual resources necessary to make a difference to life in Mumbai’s inhabited sea.

This project received financial support from the Society for Environment and Architecture, Mumbai, and the University of Pennsylvania Institute for the Advanced Study of India for The Inhabited Sea collaboration. Our work owes much to the thoughtful suggestions of colleagues with whom we delved collectively in The Inhabited Sea of stimulating conversations over several workshops. We hope that you will be able to recognize your contributions in the stories that follow. Nikhil Anand and Lalitha Kamath, we cannot thank you enough for nurturing our work in conversations with you beyond the life of The Inhabited Sea collaboration. Finally, we would like to dedicate this novel to the efforts our commune at the School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) - our colleagues, trustees, research fellows, students - for co-shaping SEA as our vibrant intellectual home, asking tough questions of this work, nurturing it with care and always rooting for us; one could not ask for more.

Chapter 1:

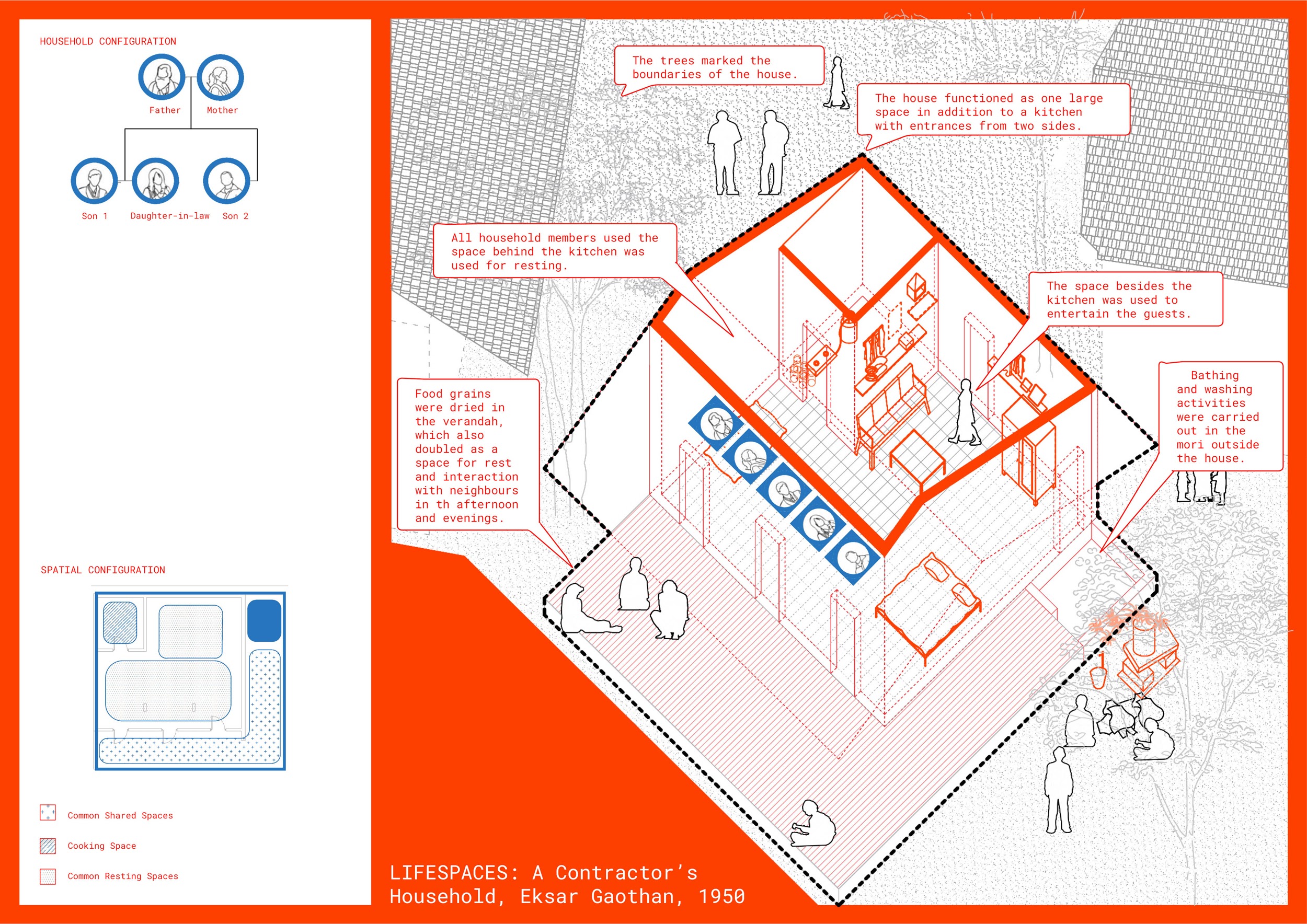

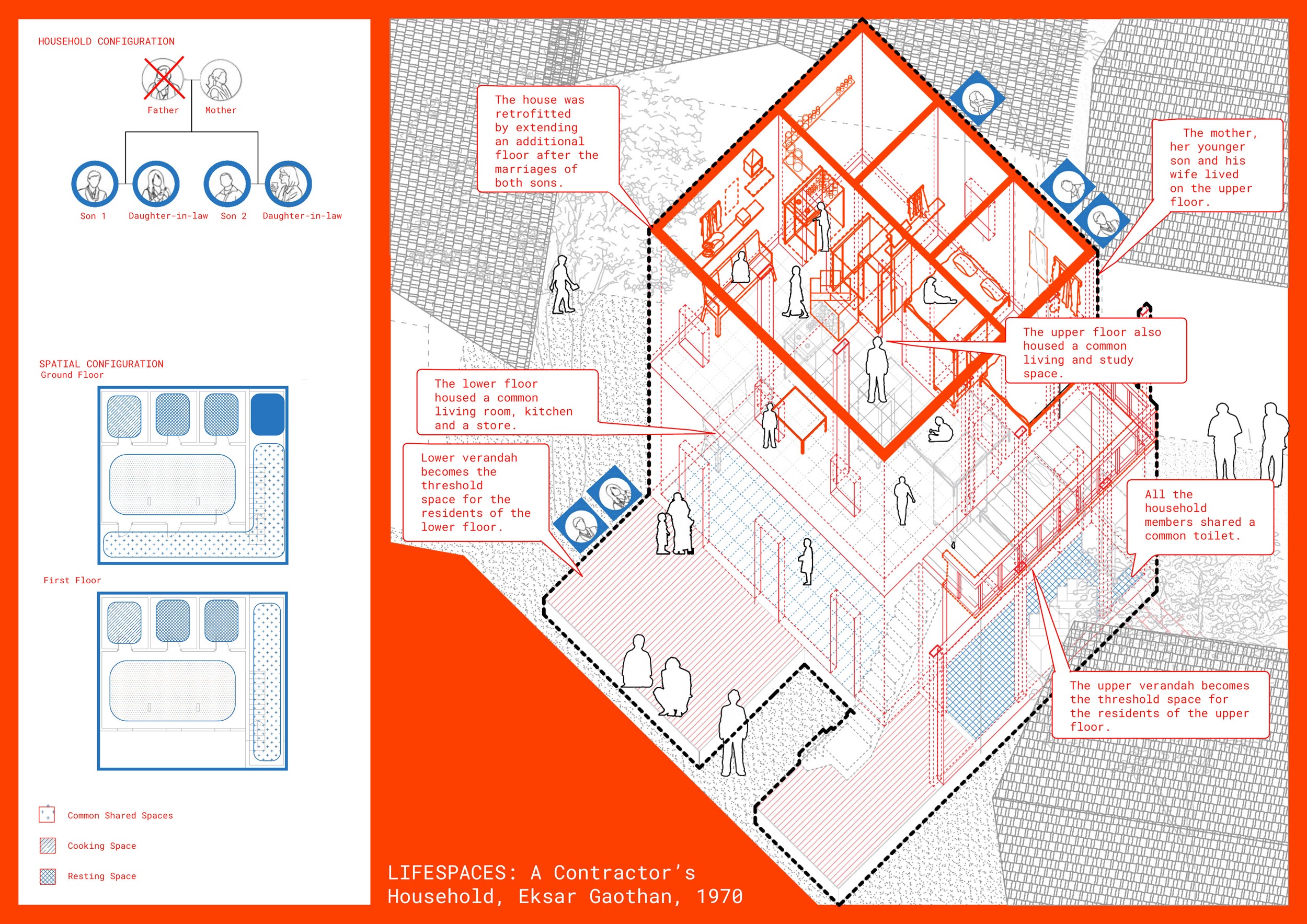

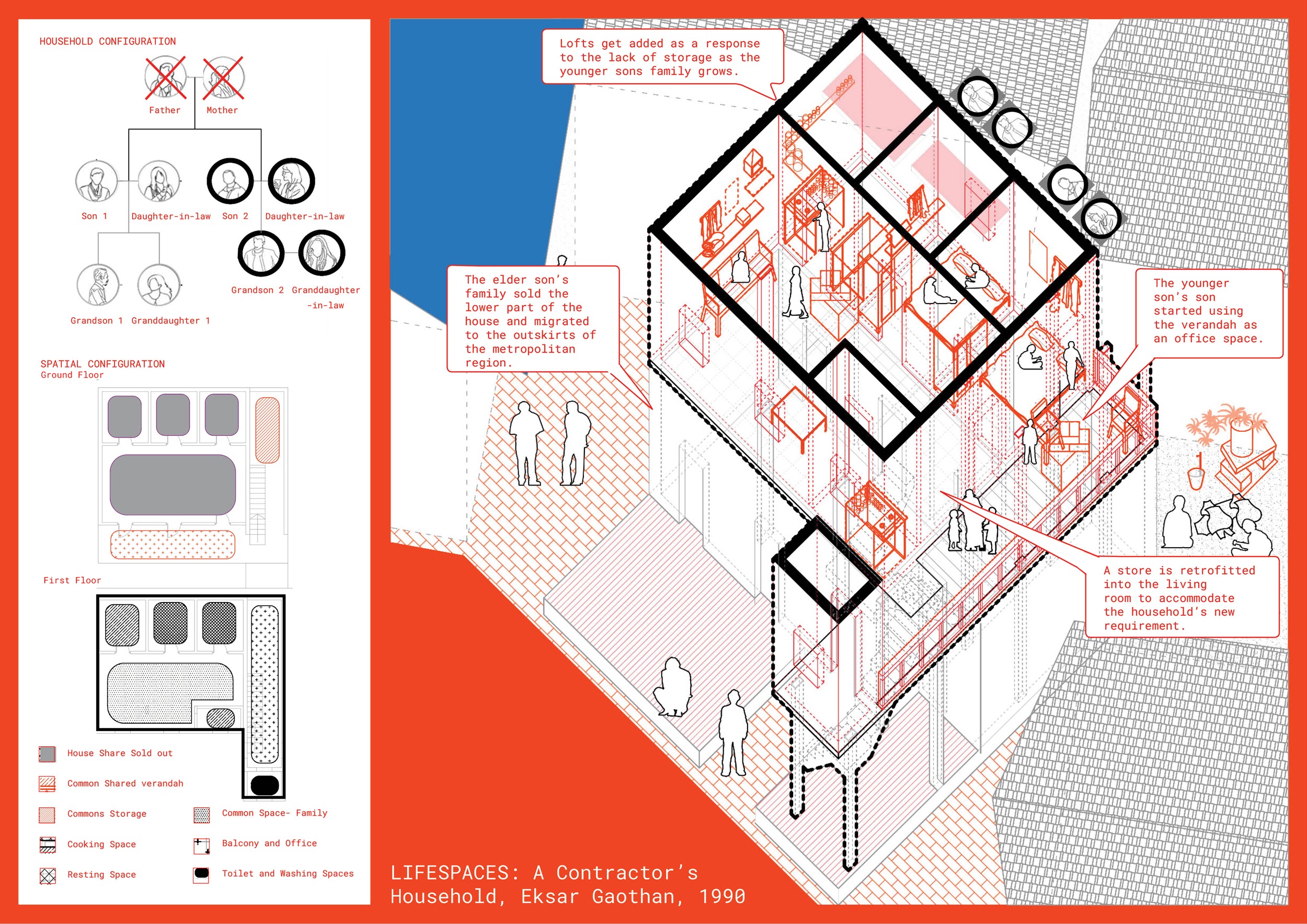

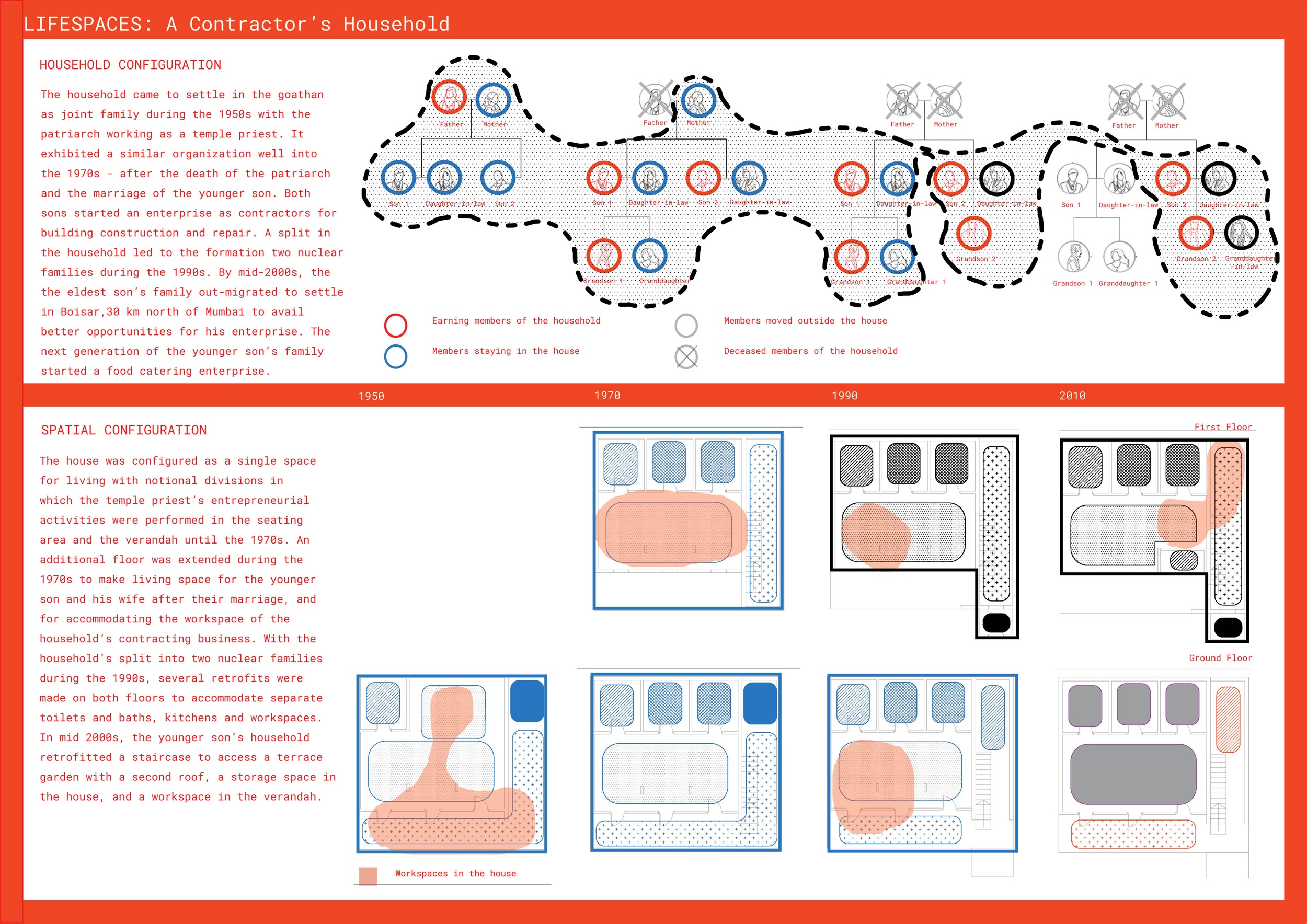

A Contractor’s Household

Chapter 2:

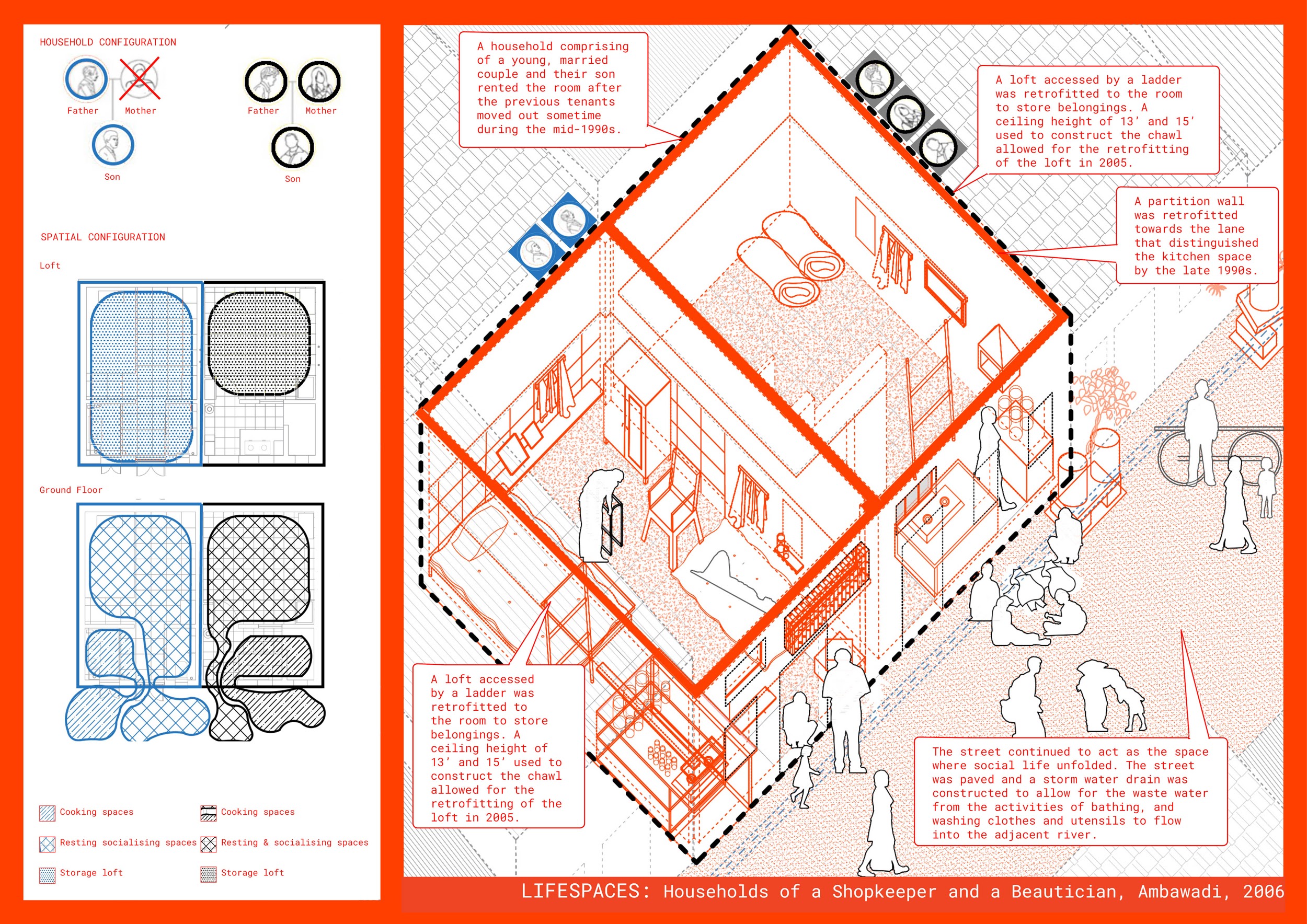

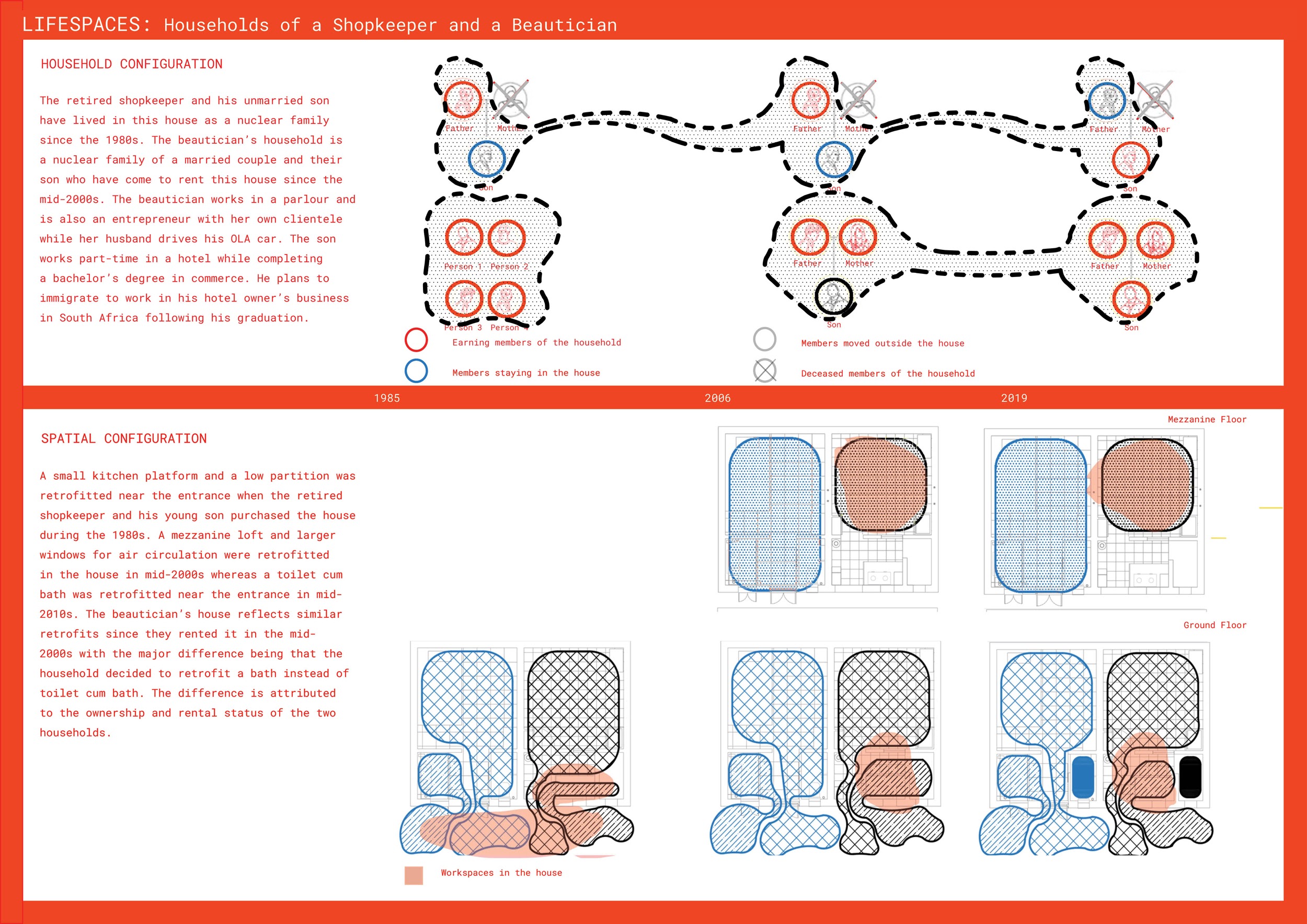

Households of a Shop Keeper and a Beautician

Chapter 3:

A Tution Teacher’s Household

Chapter 4:

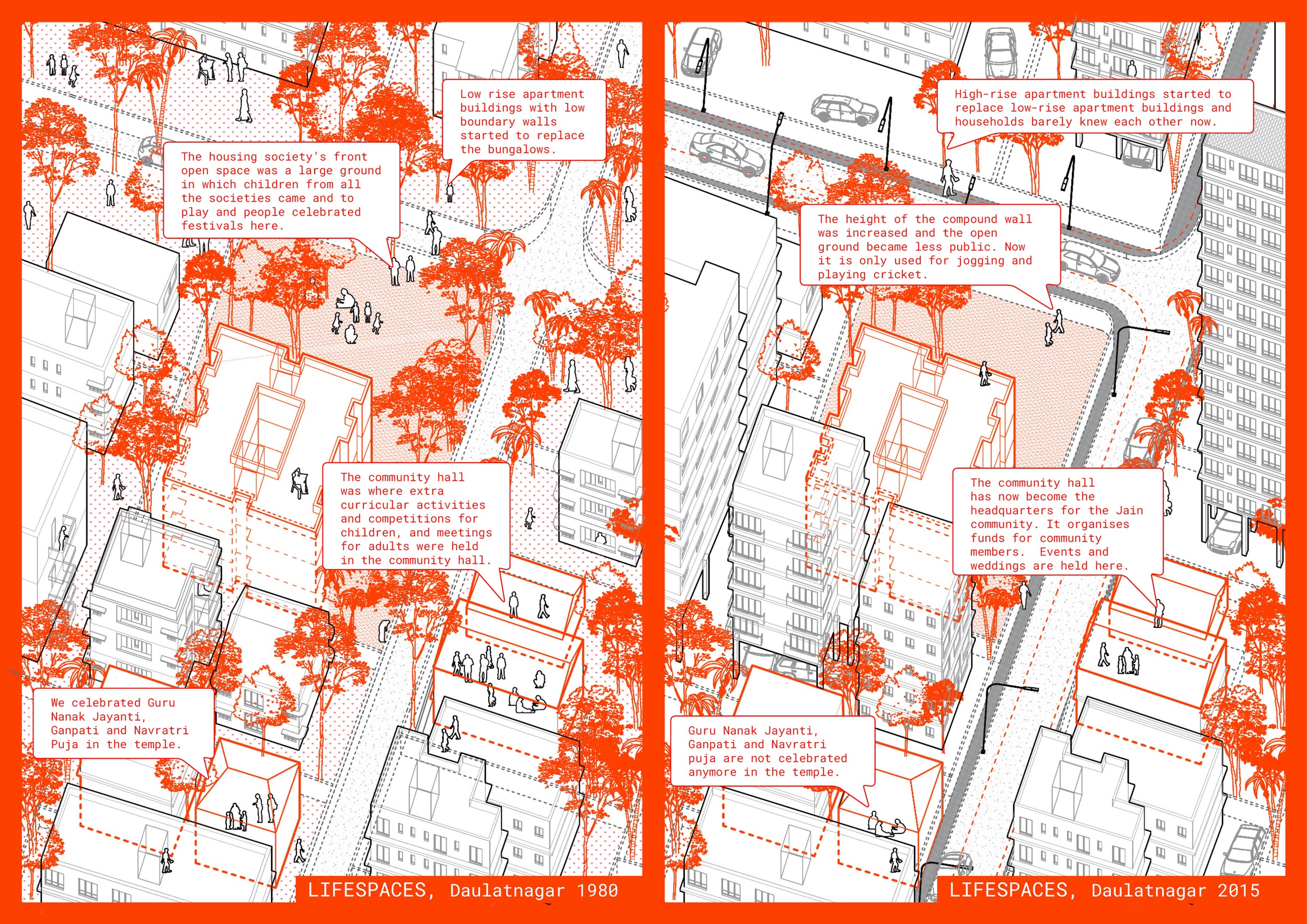

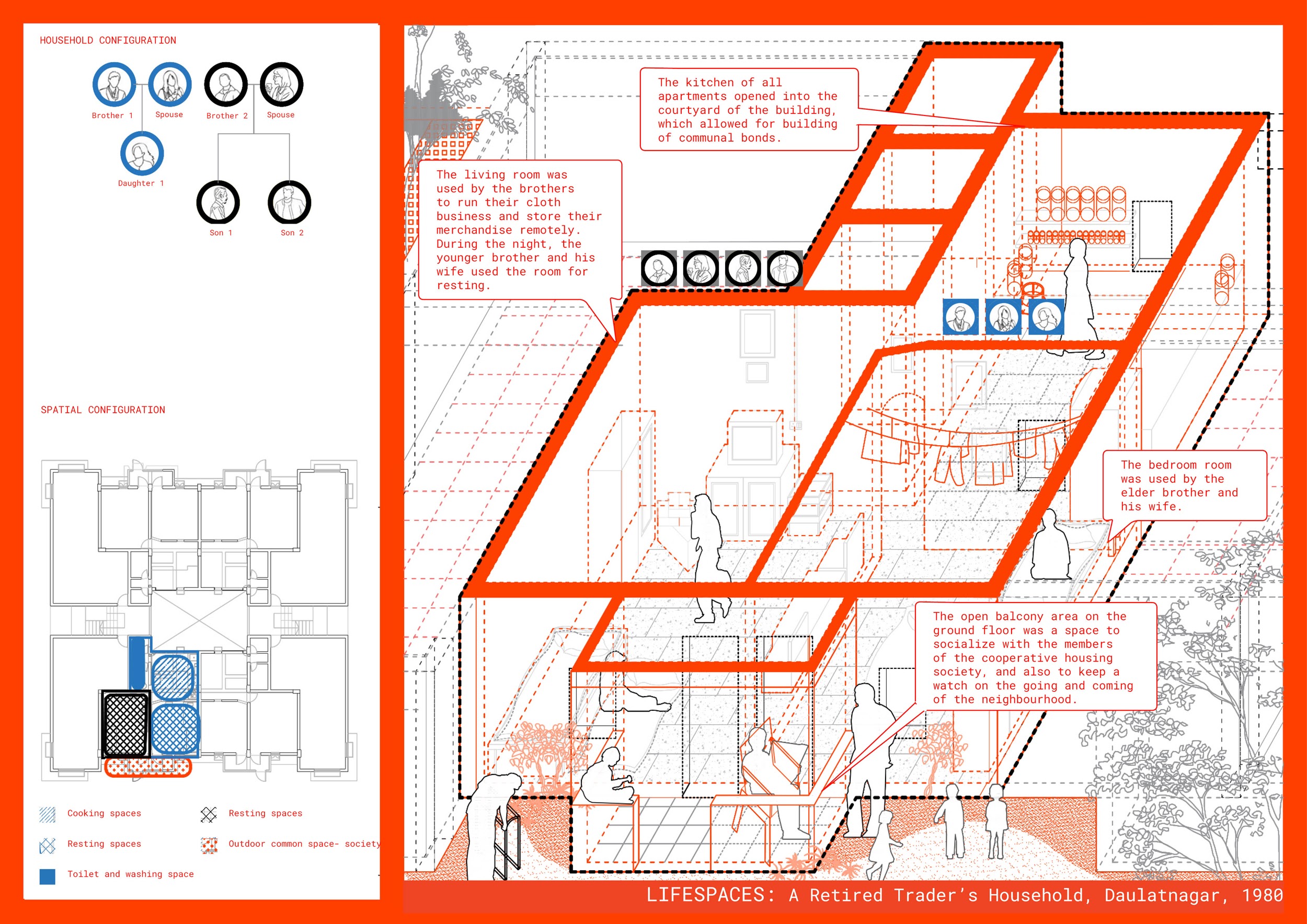

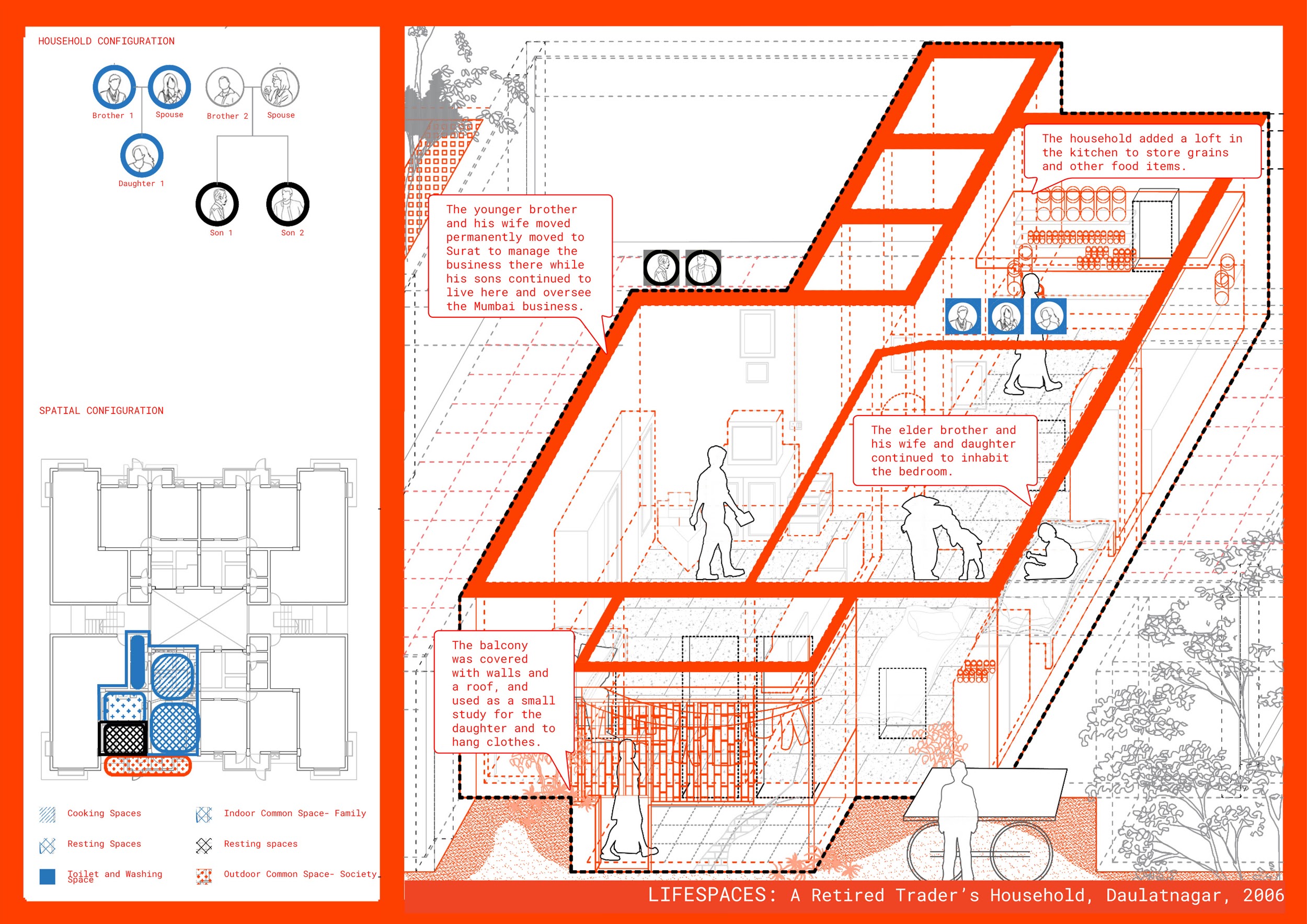

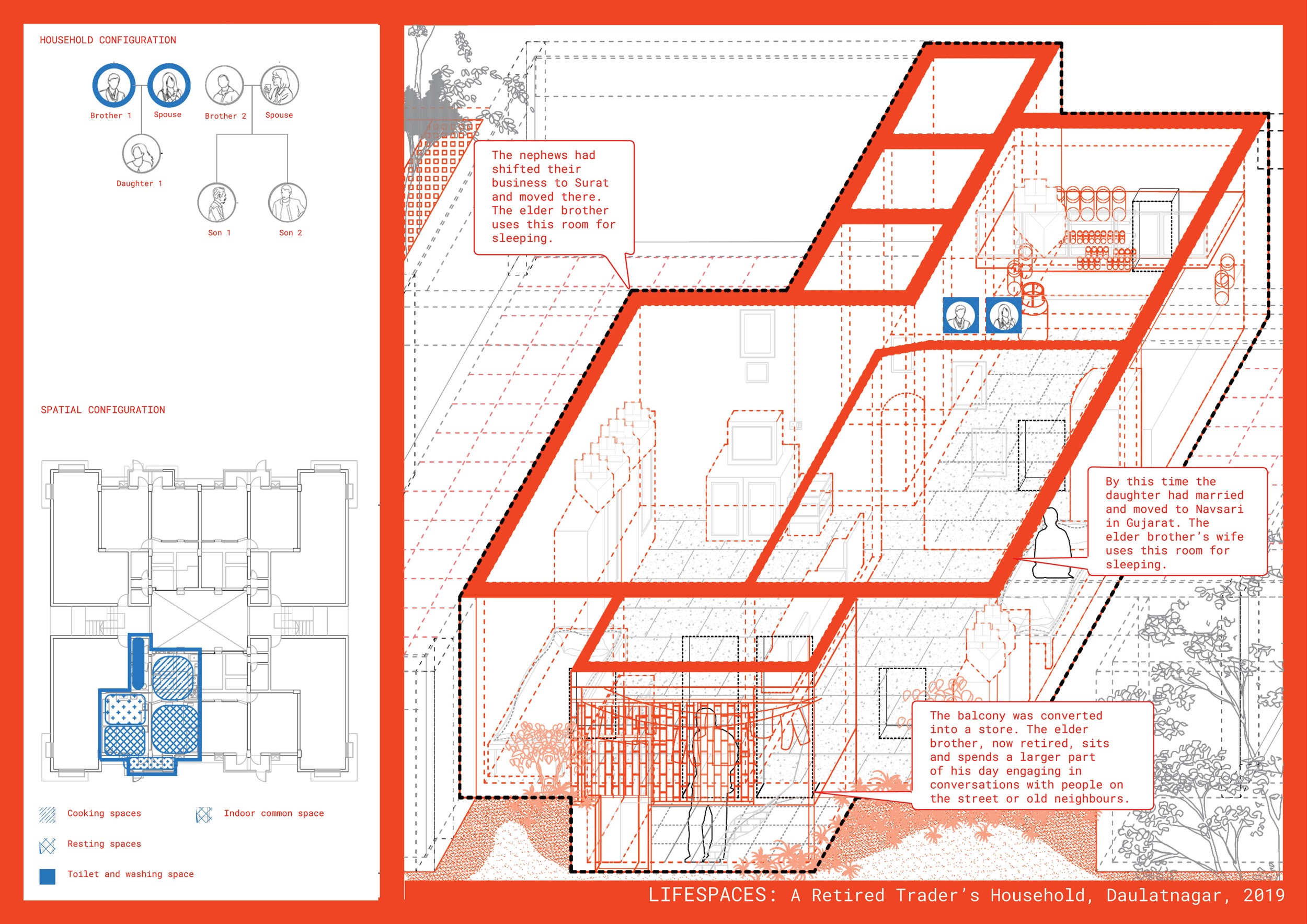

A Retired Trader’s Household

Chapter 5:

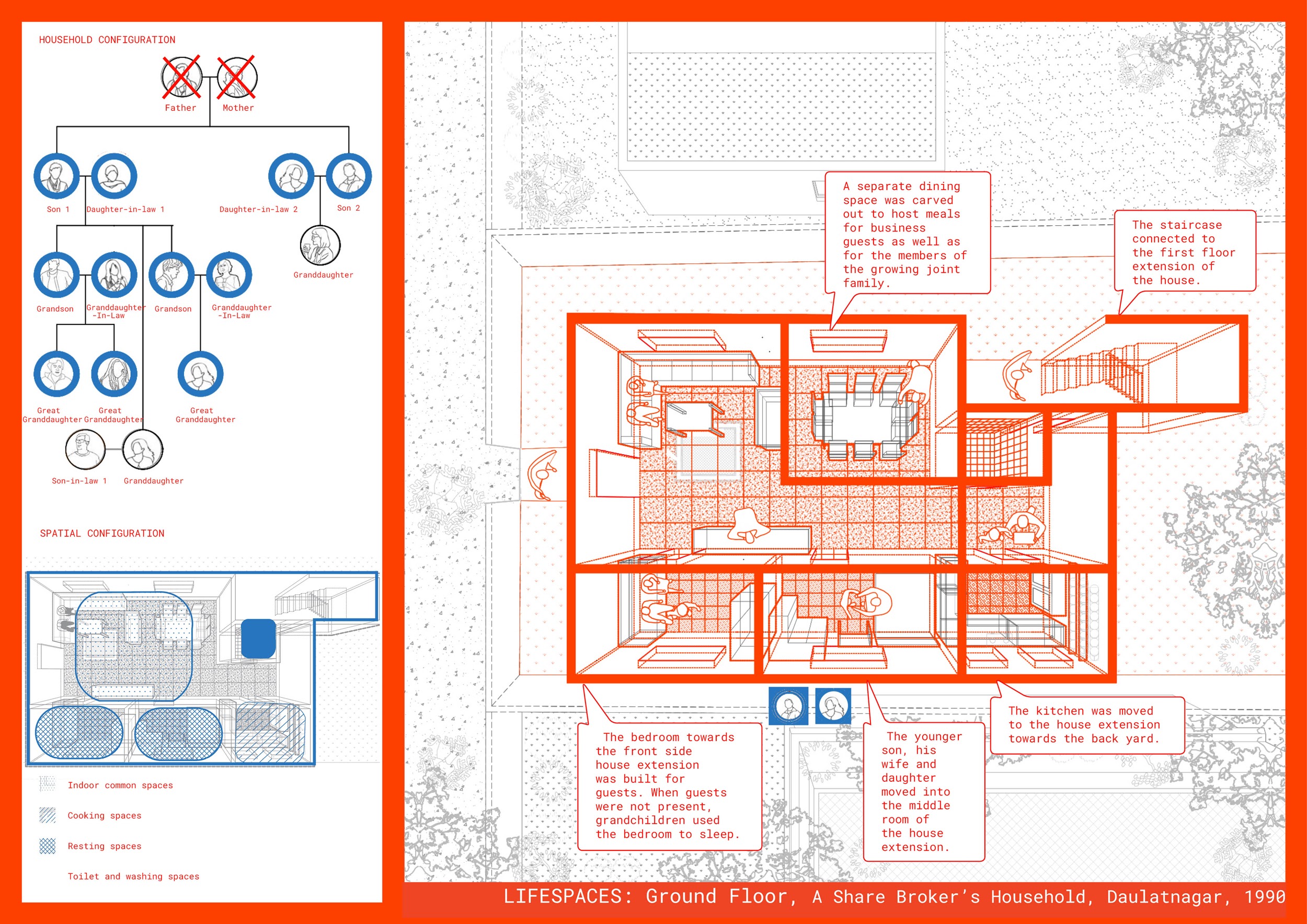

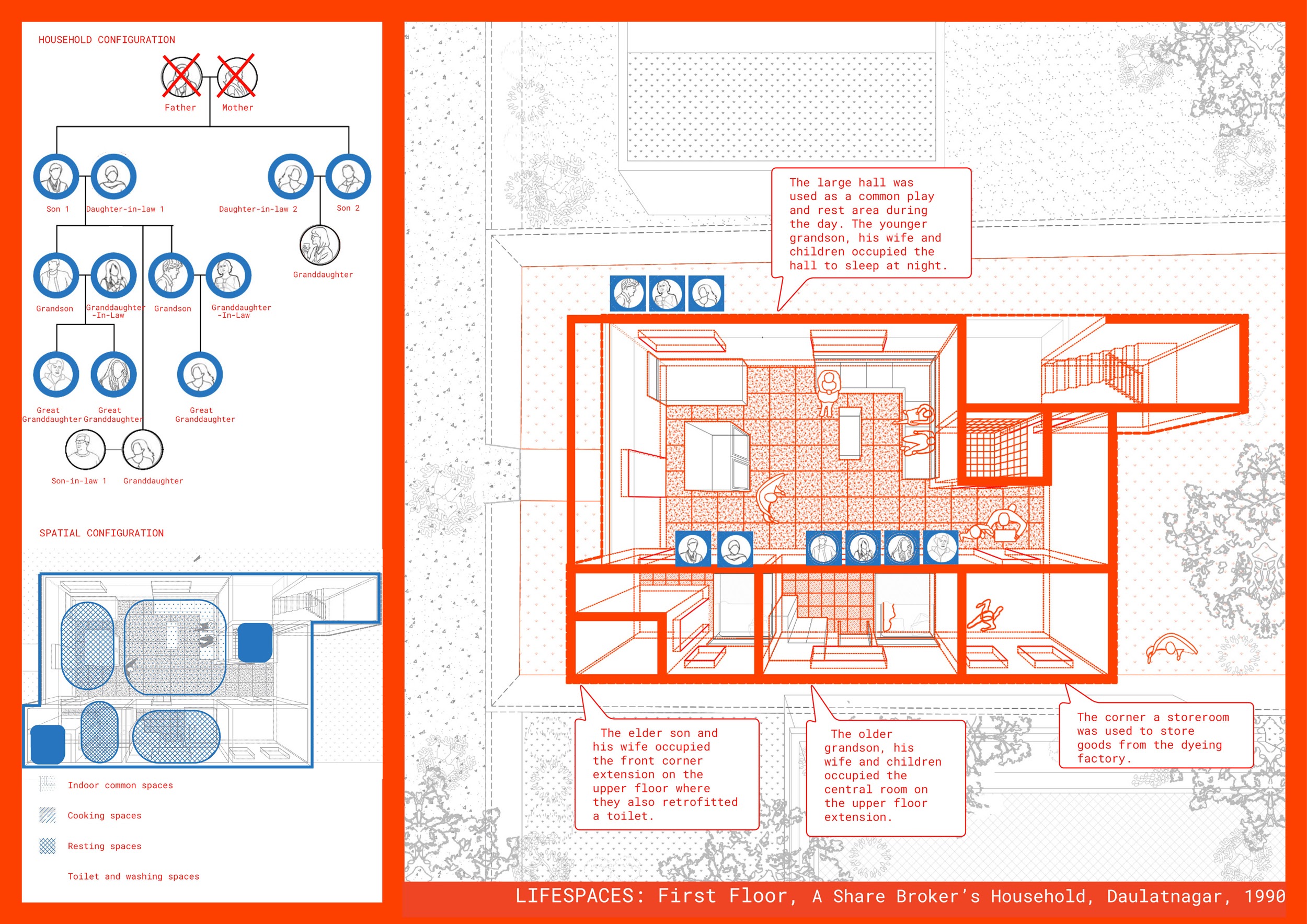

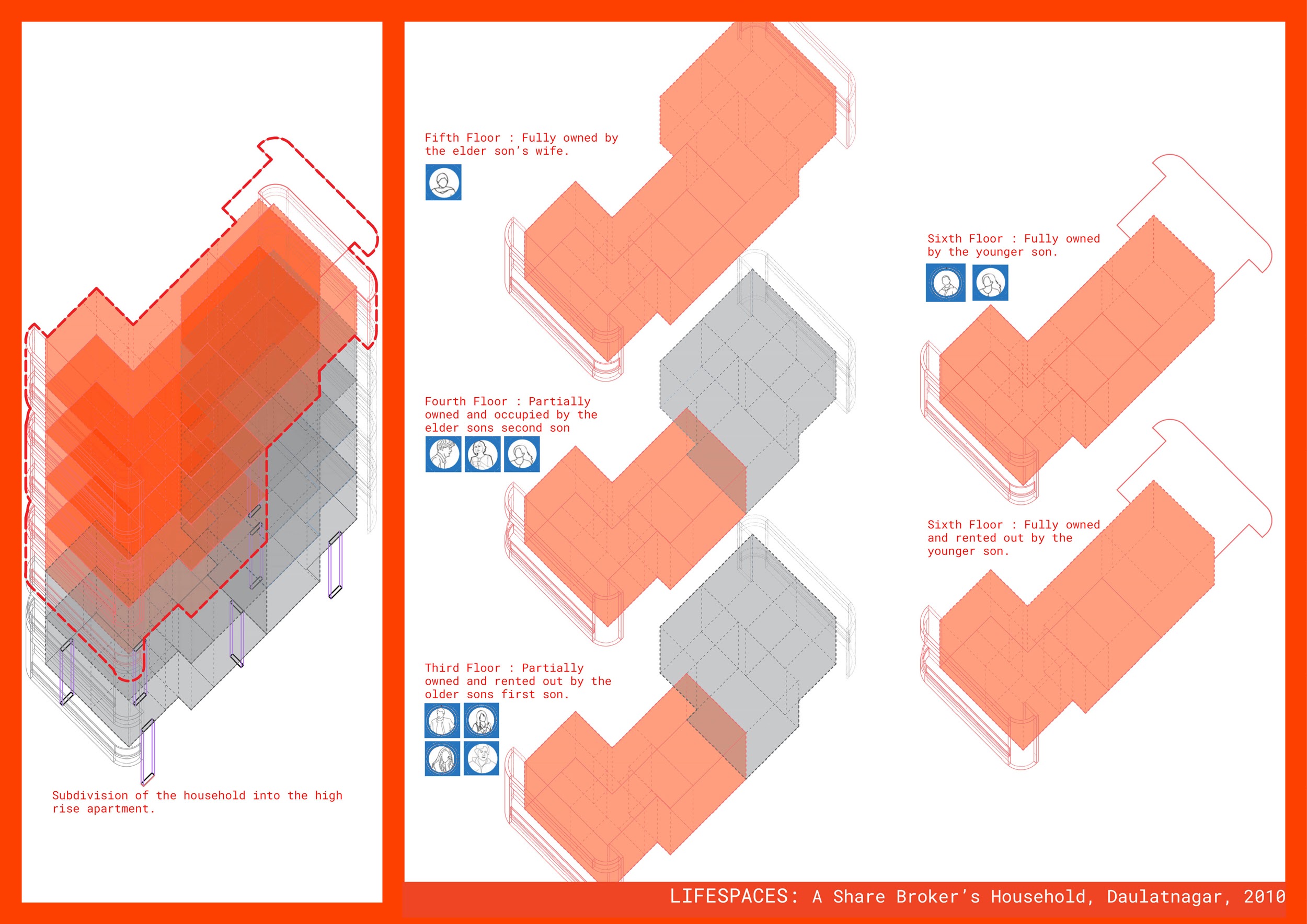

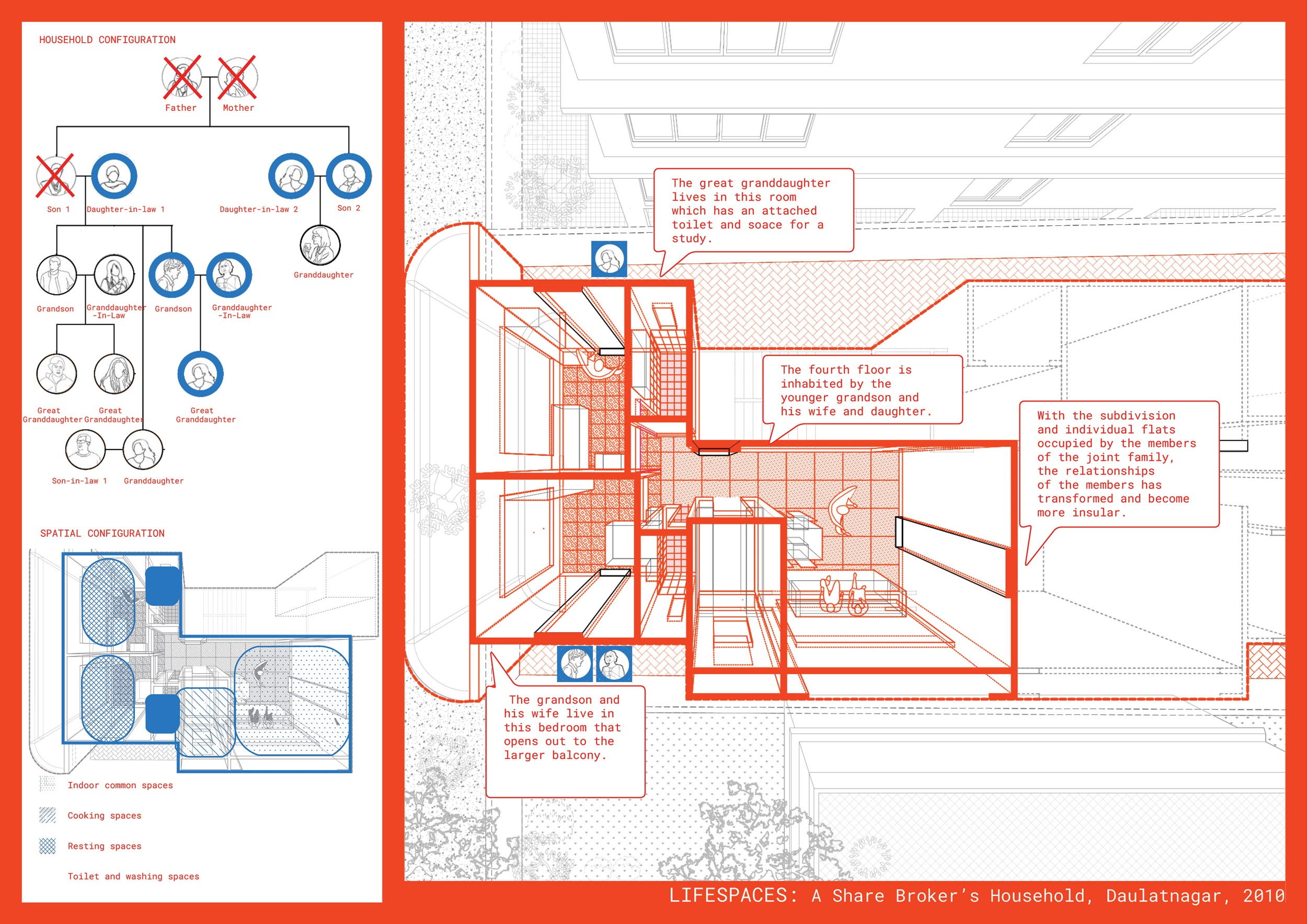

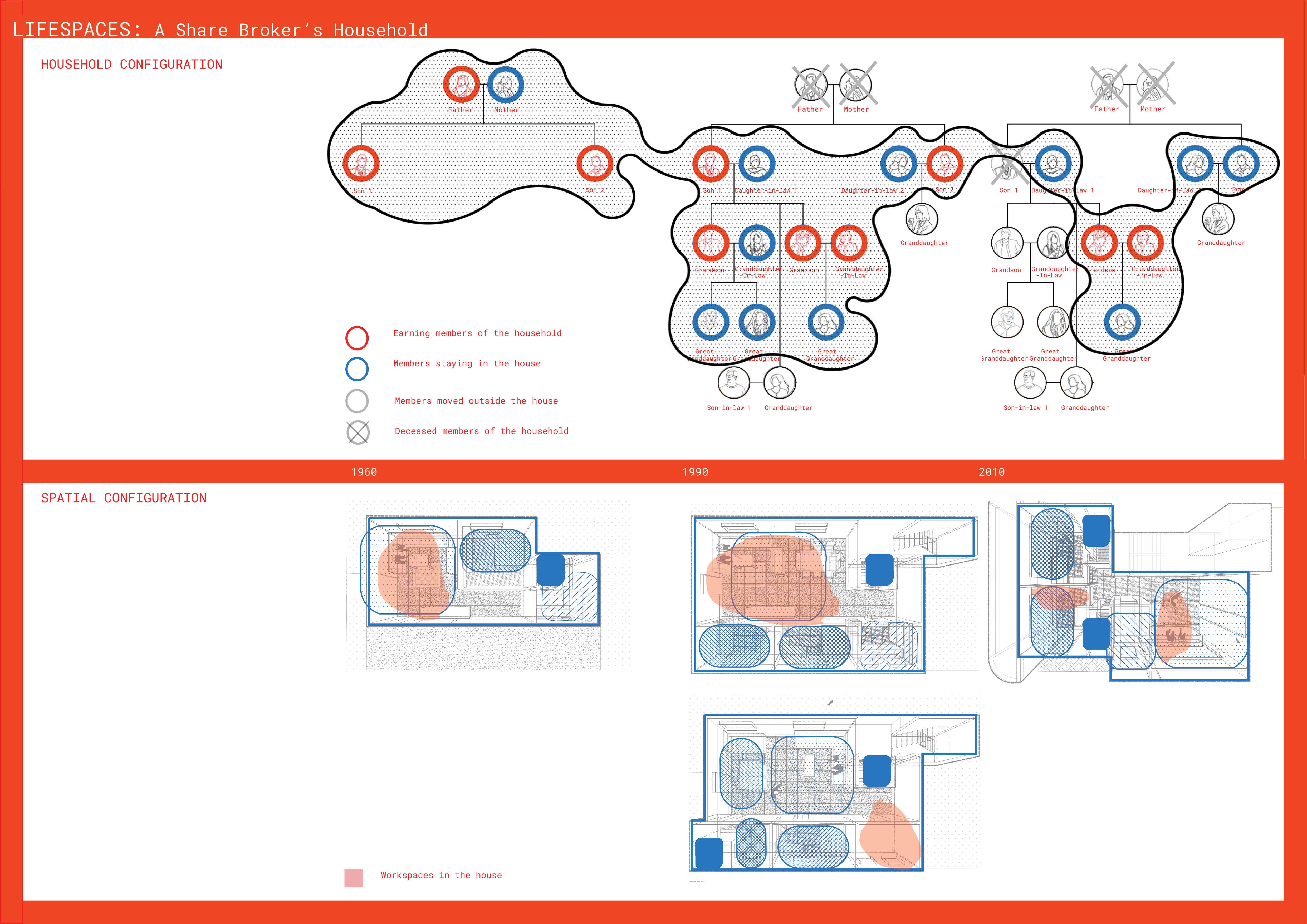

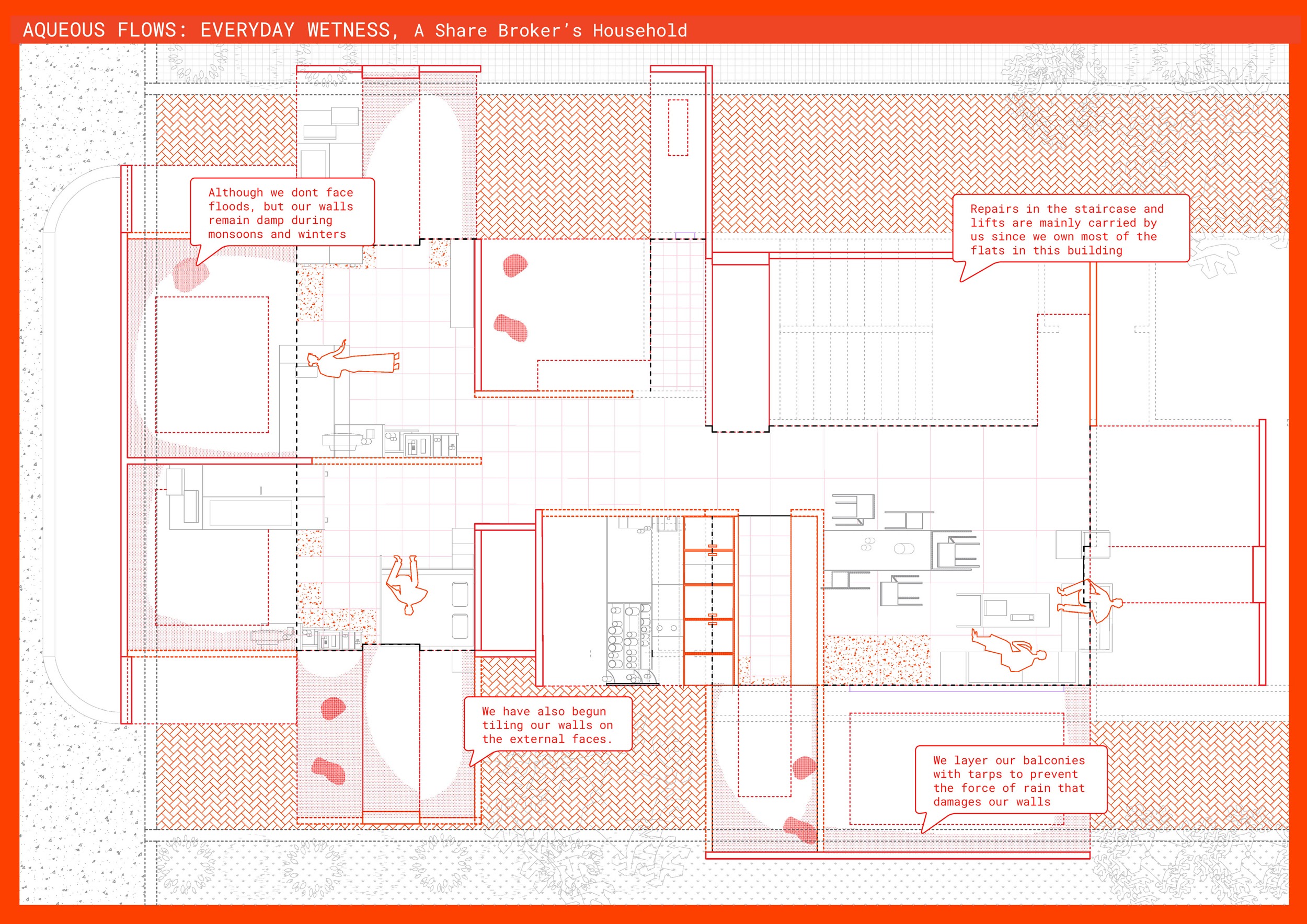

A Share Broker’s Household